Mitigation of

Circular Debt

CIRCULAR DEBT ITS CAUSES AND REMIDY

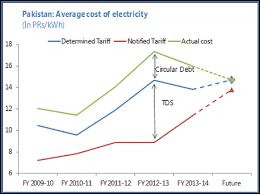

Pakistani power and energy sector is beset with

financial woes , this has tesulted in what is called circular debt .Circular

debt is an issue that has various agency. a detailed study was commissioned by

US AID ( March 2013), the study presented the causes, estimtes and remdies for

the circualr debt issues. Ministry of Water and Power presented a policy paper

in 2015 (Managing Cicrular Debt , Septemebr,2015) . The paper presented an anlsysi if the

ciauses of circular debt and prseseneted a plan to contin and mitigaite the

circular debt issues. The Papers targres are presented as follows :

Circular Debt Flows B.Rs.

|

||||||

Actual

|

Projected

|

|||||

Description

|

2015

|

2016

|

2017

|

2018

|

||

Sector Inefficiencies

|

||||||

Line Losses

|

49937

|

31950

|

17948

|

10533

|

||

Tube wells

|

33504

|

2328

|

2377

|

2253

|

||

FATA & Private

receivables

|

41058

|

41398

|

25937

|

21280

|

||

Tariff induced Inefficiencies

|

||||||

Late Payment Surcharge

|

8272

|

4971

|

3950

|

1658

|

||

Debt service

Determination delays

|

22558

|

|||||

Fiscal & Govt

Inefficiencies

|

||||||

Determination delays

|

10600

|

7600

|

4560

|

1824

|

||

AJ&K

|

15238

|

|||||

GST non refund

|

14296

|

|||||

Govt receivables

|

13831

|

3420

|

1893

|

1454

|

||

Total

|

209294

|

91667

|

56665

|

39002

|

||

The Government /

Power sector institutions have largely achieved the above stated targets. . This success , however, masks shortcomings like :

continued subsidization of domestic cutomers by industrial cuatomers ;

reduction in theft ; reduction of technical losses to regional and

international norms ; 100% recoveries ; FATA and AJ&K power issues ;

regulatory refoms ; and privatisation have not revieved the attention these

desercved.

Way Forward

The PMLN Government took eradication of load shedding as their election

manifesto and after the election resolved to fulfill this promise. This

resulted in, more than usual, involvement of Government in affairs of Power

Sector entities .This needs to change Government needs to:

1.

Distance itself from the governance of the power sector, control of entities should be given to corporate bodies

and given independence

2.

GoP needs to support NEPRA to put in place a more competitive power

sector. A road map to a competitive, market must be approved across the

political divide and the plan must be set rolling with c ear goal and timeline.

3.

Tariff and subsidy disputes between Provinces, CPPA and DISCOs need to

be settled by negotiations or arbitration.

4.

Legislation making theft of electricity a crime with specific

punishments mentioned .and specialized courts established to implement this .

5.

The selection criteria for appointment of DISCOs Board of Directors need

to be improved. Members need to have high professional and technical

capabilities , be independent of political influence and have full authority

for decision making .Training to effectively monitor performance and enforce

accountability needs to be imparted to prospective candidates of BoDs.

6.

Eliminate the tariff equalization regime and gradually move to Regulator

determined tariff based on true costs. The current cross subsidy between better

performing DISCOs and poor performing DISCOs need to be eliminated.

7.

Implement a strong program for energy conservation , demand side

management and efficiency

8.

Measures that promote local sources of energy need to be given special

attention. Local coal, Hydropower, solar electrification of tube wells, solar

panels for home use in rural and even urban areas needs to be pushed. There is

also need to push used of solar for heating applications in Industry and homes,

both are competitive.

Background

Circular debt (CD)

occurs when one entity in the power chain is unable to pay suppliers this

affects others players as well who are also unable to fulfill their financial

obligations. This results in increase in generation costs and unnecessary load

shedding as many players in the power chain have defaulted and lest cost

dispatch is not possible. Circular debt arises when

one party not having adequate cash flows to discharge its obligations to its

suppliers withholds payments. When it does so, the problem affects other

entities in the supply chain, each of which withholds its payments, resulting

in operational difficulties for all service providers in the sector, none of

whom are then able to function at full capacity, causing unnecessary load

shedding.

CD is the amount of payables within the Central Power Purchasing Agency (CPPA) that it cannot pay to power generation companies (Independent Power Producer (IPP), government owned thermal generation companies (GENCOs), the hydropower producer (WAPDA Hydel) and National Transmission & Despatch Company (NTDC). The revenue shortfall cascades through the entire energy supply chain, from electricity generators to fuel suppliers, refiners, and producers; resulting in a shortage of fuel supply to the GENCOs and IPPs and thereby reduce power generation and thus increase in load shedding.

The cause of

circular debt includes:

1.

Poor governance

2.

Delay in tariff

determination by an inadequately empowered regulator compounded by interference

and delay in notification by the Government of Pakistan (GoP).

3.

A fuel price

methodology that delays the infusion of cash into the system

4.

Poor recoveries of energy billed by DISCOs

5.

Delayed and

incomplete payments by the Ministry of Finance on Tariff Deferential Subsidy

(TDS) and Karachi Electric (KE) contract payments.

6.

NEPRA sets tariff

at 100% recoveries whilst DISCOS have managed to collect between 86% to 94%

receivables in various years in the last 10 years or so.

7.

High power loss due to theft and the gap between NERA allowed

losses in tariff setting and actual losses incurred by DISCOs and NTDC .

8.

Inability of DISCOs to pass entire fuel cost to customers due to

court stay orders.

9.

Increase in receivable for both public and private customers.

10. Lower efficiencies and higher O&M cost of publically owned

generation companies (GENCOs) than those allowed by NEPRA in tariff setting.

11. Payment of GST upfront in

billed amount

The circular debt numbers that get reported in the press tend to

be the sum of the receivables of each organization which ends up exaggerating

the amount, simply because of double counting. After all, one party’s payables

are the other party’s receivables, and logically these should cancel out when

we subtract one from the other. At worst the net amount should be much smaller.

The oil marketing companies sell oil to the IPPs or the

Wapda-owned electricity generation plants (called Gencos) which produce

electricity and sell it to the government-run distribution companies referred

to as DISCOs (for example Lesco, Pesco, etc) which provide power to our homes

and factories and bill us for this service. The tariff (price) at which the

Gencos sell to the DISCOs and the tariff at which electricity is supplied to us

consumers is determined by Nepra, after receiving government approval.

The first problem which results in the receivables not

cancelling out payables is when the tariff is unable to meet the costs of its

generation and distribution. For instance, if the price of oil goes up

internationally and tariffs are not revised upwards to account for this

increase, there is an element of subsidy whose cost the government has to pick

up. So one component of what constitutes circular debt is the lower rate at

which electricity is being charged to the consumer than the cost of its

generation and distribution. By failing to foot this subsidy bill the

government builds up the circular debt. The bulk of the issue arising from the

failure to revise tariffs upwards on a timely basis has been resolved; the

remaining adjustment required on this account is Rs100bn for this year, which

also includes the cost of poor governance.

Next, three components, and the most critical ones, which raise

costs, and feed the circular debt, are the following:

— The inefficiencies of government-owned generation and

distribution companies, overstaffing , poor maintenance of plant equipment,

obsolete technologies (resulting in technical losses), corruption, all of which

simply add to the cost of electricity that consumers are being constrained to

bear with equanimity through tariff increases.

— The massive issue of electricity theft — the cases of DISCOs

in Hyderabad, Peshawar, Quetta and Fata are now well known; with literally no

one paying in Fata.

— Poor collection of electricity bills.

To summaries, the issues are failures to revise electricity

tariffs on a timely basis; prevent electricity theft; and ensure collection of

billings speedily and disconnecting those not paying their bills;

disconnections will actually also reduce the extent of outages/load shedding.

In other words, the principle issue is that of governance.

GENCOs

Publically

owned power generation companies or GENCOs are allowed efficiencies that are

lower than the actual de-rated efficiencies of their plants. The allowed tariff

to these GENCOs, by NEPRA, does not in fact cover costs. GENCO tariffs are based on the heat rates of generating units. The heat rate is defined as

the amount of fuel consumed for each unit (kWh) generated. Over time, as efficiencies of generating units have declined, heat rates have increased. The higher the heat rate of the

plant, the greater the amount of fuel consumed per unit of electricity generated. There are

some allegations of fuel thefts

at the GENCOS, which also results in lower efficiency. However, for tariff determination, NEPRA uses lower heat rates versus the actual GENCO

rates as shown in below:

HEAT RATES GENCOS and NEPRA ALLOWED HEAT RATES

|

|||

Diff

|

|||

GENCOs

|

NEPRA

|

Actual

|

%

|

CPGCL (GENCO I)

|

|||

Block 1

|

8,533

|

9,153

|

7.27

|

Block 2

|

9,481

|

10,200

|

7.58

|

Block 3

|

11,377

|

13,109

|

15.22

|

Block 4

|

12,189

|

14,041

|

15.19

|

NPGCL (GENCO III)

|

|||

Unit 1-3 (TPS

Muzaffargarh)

|

10,788

|

11,677

|

8.24

|

Unit 4 (TPS Muzaffargarh)

|

10,692

|

11,087

|

3.69

|

Unit 5-6 (TPS

Muzaffargarh)

|

12,158

|

14,164

|

16.50

|

Units 1-2 (SPS

Faisalabad)

|

14,368

|

14,156

|

-1.48

|

Units 1-4 (GTPS

Faisalabad)

|

15,366

|

17,708

|

15.24

|

Units 5-9 (GTPS (Faisalabad)

|

11,701

|

10,259

|

-12.32

|

Unit 1-3 (Multan)

|

14,114

|

16,169

|

14.56

|

JPCL (GENCO II)

|

|||

Unit 1 (Jamshoro)

|

10,655

|

11,505

|

7.98

|

Units 2-4 (Jamshoro)

|

10,862

|

12,930

|

19.04

|

Unit 1-2 (Kotri)

|

21,813

|

22,353

|

2.48

|

Units 3-7 (Kotri)

|

10,564

|

11,902

|

12.67

|

The price of power delivered by the GENCOs is

underestimated as it does not reflect the true cost of fuel to the GENCOs. This reduces the

GENCOs’ income, resulting in cash flow difficulties, which causes the GENCOs to postpone

maintenance and

other essential expenses, including payment to fuel suppliers.

A heat rate audit needs to be conducted to establish new benchmark heat rates for NEPRA to use for

tariff determinations. Until this audit is conducted, NEPRA cannot update its heat rate figures

for use in setting tariffs for the DISCOs.

In recent rulings NEPRA has allowed GENCOs and

KE plants to carry out independent efficiency audits , these tests are also to

be supervised by NEPRA .

GENCOs O&M Rates

NEPRA does not allow the actual GENCOs O&M costs, this

result in lower recoveries than cost by GENCOs.

NTDC LOSSES

The NTDC also failed in keeping its transmission losses for the 500/220

kV transmission network within NEPRA-approved limits Presented as follows

NTDC actual and NEPRA allowed losses

|

||||||||||||

Growth %

|

Growth %

|

Growth %

|

||||||||||

2009

|

2010

|

2011

|

2012

|

2013

|

2014

|

2015

|

2016

|

FY 09-13

|

FY13-16

|

FY13-16

|

||

Allowed

|

%

|

2.5

|

2.5

|

2.5

|

2.5

|

2.5

|

2.5

|

2.5

|

2.5

|

|||

Units for Trans

|

GWh

|

82702

|

87115

|

90575

|

88987

|

87080

|

94089

|

95979

|

100871

|

1.30

|

5.02

|

2.88

|

Losses

|

GWh

|

2959

|

2740

|

2740

|

2508

|

2656

|

2587

|

2620

|

2623

|

-2.66

|

-0.42

|

-1.71

|

Losses

|

%

|

3.58

|

3.15

|

3.03

|

2.82

|

3.05

|

2.75

|

2.73

|

2.60

|

-3.91

|

-5.18

|

-4.46

|

Diff

|

1.08

|

0.65

|

0.53

|

0.32

|

0.55

|

0.25

|

0.23

|

0.10

|

-15.48

|

-43.28

|

-28.76

|

|

Had the high transmission losses

been restricted to the regulatory target, the accumulation of circular debt in

FY 2009, FY 2010, and FY 2011 could have been reduced by Rs11 billion and over

40 MW capacity released, reducing load shedding by this amount close to the

Regulator allowed losses . The above suggests that there is increased economic

activity in the period 2013 to 2016 than in the period 2009 to 2013 there has been a steady decrease in losses,

with increased investment in transmission it is likely that transmission losses

will be within the regulator set limits although transmission demand is also

growing. and the regulator set losses targets are moving targets ..

Tariff

Differential Subsidy (TDS)

NEPRA determines tariffs based on

analysis for all customers in all DISCOs, these differ widely among DISCOs. ,

the Government deems it essential to have the same tariff for the same type of

customer for all DISCOs. NEPRA law does not allow tariff be set above the one

determined by NEPRA. This therefore requires that the tariff for each customer

category class be set equal to the lowest such tariff determined by NEPRA. This

also means that Government will have to pick up the difference. This subsidy to

equalize tariff forms a major part of the circular debt since the government

subsidy is not always equal to the requirement and it is not always paid in

time. The following is an example of how TDS works.

TARIFF DIFFERENTAIL SUBSIDY - CALCULATION 2011-12

|

|||||

Subsidy

|

|||||

Consumer

|

NEPRA

|

Gov

|

Subsidy

|

Subsidy

|

% Total

|

Rs,/kWh

|

Rs,/kWh

|

Rs./kWh

|

M.Rs.

|

%

|

|

Domestic upto 50

|

3

|

2

|

1

|

2300

|

0.64

|

Domestic 01-100

|

9.9

|

5.8

|

4.1

|

54200

|

15.09

|

Domestic 101-300

|

13.1

|

8.1

|

5

|

55000

|

15.32

|

Domestic 301-700

|

15.5

|

12.3

|

3.2

|

12300

|

3.43

|

Domestic over 700

|

17.2

|

15.1

|

2.1

|

2800

|

0.78

|

Domestic Total

|

126600

|

35.25

|

|||

Commercial

|

14.4

|

11.4

|

3

|

12400

|

3.45

|

Industrial

|

12.9

|

10.3

|

2.6

|

54000

|

15.04

|

Bulk Supply

|

13.1

|

10.3

|

2.8

|

4000

|

1.11

|

Tube wells

|

12.6

|

9.4

|

3.2

|

28000

|

7.80

|

Others

|

14.1

|

10.8

|

3.3

|

7500

|

2.09

|

Total

|

12.57

|

9.55

|

3.02

|

359100

|

|

Delay in Notification of the

Decisions/Determinations of the Authority:

Upon intimation by the Authority and non-submission of the

re-consideration request, the Federal Government pursuant to Section 31(4) of

NEPRA Act, is required to notify the Authority’s approved tariff, rates,

charges, and other terms and conditions for the supply of electric power

services by generation, transmission and distribution companies, in the

Official Gazette, within 15 days. As per NEPRA record, a large number of

notifications (79Nos, in 2015) in respect of NEPRA’s determinations/decisions,

were pending with Ministry of Water and Power, either for notification or of

notified,

Delays in tariff determination and notification contributed

Rs72.19 billion11 to the circular debt for FY 2012. Tariff determinations for

all nine DISCOs were delayed for nine months and it took an additional month

for the notification to be published. Consumer tariffs in 2011-12 were largely

based on 2010-11 tariff values whereas the actual fuel cost for 2012 was 52%

higher than the previous year. Without new tariff values from NEPRA and the

GOP, the DISCOs had no chance to receive the necessary cash required to meet

their monthly wholesale power cost.

Once NEPRA determines the tariff, the GOP reviews it and

officially notifies a tariff after modifications as deemed appropriate.

Although NEPRA has reduced the time it takes to determine tariffs, the

determination procedure still takes many months. In addition, tariff setting

lacks independence, as the GOP notification process often results in a delay

and/or reduction in the tariff due to political considerations.

The Government in 2015 issued a paper

that intended to reduce Circular Debt. The objectives were:

1.

Maintain a cap of Rs. 314 billion on the Circular Debt

2.

Reduce circular debt from Rs. 314billion ( end June 2015) to Rs 212 billion by FY2018 and

3.

Reduce PHCL debt from Rs 335 billion to Rs 220 billion by FY2018.

These objectives were to be

achieved by the following measures:

Improved

Efficiencies.

The strategy for improving efficiency was based on a gradual decrease in the losses and increase in the collections from consumers. Working on the same strategy, collections have seen an improvement in FY 2015 in the range of 89.2% as opposed to the previous rate of recoveries in FY 2014 of 87%. Losses stabilized at 18.7% in the same period. The plan for management of CD until the end of FY 2018 is based on the same strategy and principles.

The objective has been partly

achieved. Recoveries are presented as follows:

Recoveries : Billings and Collections DISCOs

|

|||||||||||||||||||

FY 2012-13

|

FY 2013-14

|

FY 2014-15

|

FY 2015-16

|

Growth

|

|||||||||||||||

Billing

|

Collection

|

Billing

|

Collection

|

Billing

|

Collection

|

Billing

|

Collection

|

Billing

|

Collection

|

Difference

|

|||||||||

DISCO

|

M.Rs

|

% share

|

M.Rs

|

% 0f Billing

|

M.Rs

|

% share

|

M.Rs

|

% 0f Billing

|

M.Rs

|

% share

|

M.Rs

|

% 0f Billing

|

M.Rs

|

% share

|

M.Rs

|

% 0f Billing

|

%

|

%

|

%

|

LESCO

|

163868

|

21.43

|

160340

|

97.85

|

226044

|

23.39

|

221239

|

97.87

|

225481

|

22.24

|

216190

|

95.88

|

233501

|

23.41

|

231638

|

99.20

|

9.26

|

9.63

|

0.38

|

GEPCO

|

63705

|

8.33

|

62588

|

98.25

|

86026

|

8.90

|

82708

|

96.14

|

90872

|

8.96

|

88272

|

97.14

|

96437

|

9.67

|

95863

|

99.40

|

10.92

|

11.25

|

0.33

|

FESCO

|

95606

|

12.50

|

94711

|

99.06

|

124665

|

12.90

|

124729

|

100.05

|

128180

|

12.64

|

128255

|

100.06

|

133330

|

13.37

|

133416

|

100.06

|

8.67

|

8.94

|

0.27

|

IESCO

|

84123

|

11.00

|

79445

|

94.44

|

110070

|

11.39

|

99519

|

90.41

|

109958

|

10.84

|

99967

|

90.91

|

113756

|

11.41

|

103460

|

90.95

|

7.84

|

6.83

|

-1.01

|

MEPCO

|

107932

|

14.11

|

99035

|

91.76

|

138621

|

14.35

|

133127

|

96.04

|

138646

|

13.67

|

141881

|

102.33

|

141677

|

14.21

|

141663

|

99.99

|

7.04

|

9.36

|

2.32

|

PUNJAB

|

515234

|

67.36

|

496119

|

96.29

|

685426

|

70.94

|

661322

|

96.48

|

693137

|

68.36

|

674565

|

97.32

|

718701

|

72.06

|

706040

|

98.24

|

8.68

|

9.22

|

0.55

|

Share %

|

67.36

|

69.26

|

|||||||||||||||||

PESCO

|

71749

|

9.38

|

60700

|

84.60

|

82921

|

8.58

|

71537

|

86.27

|

105933

|

10.45

|

93258

|

88.03

|

91672

|

9.19

|

81119

|

88.49

|

6.32

|

7.52

|

1.20

|

TESCO

|

15025

|

1.96

|

17948

|

119.45

|

15740

|

1.63

|

1264

|

8.03

|

15072

|

1.49

|

11472

|

76.11

|

4692

|

0.47

|

20507

|

437.06

|

-25.25

|

3.39

|

28.63

|

NWFP

|

86774

|

11.35

|

78648

|

90.64

|

98661

|

10.21

|

72801

|

73.79

|

121005

|

11.93

|

104730

|

86.55

|

96364

|

9.66

|

101626

|

105.46

|

2.66

|

6.62

|

3.96

|

Share %

|

11.35

|

10.98

|

|||||||||||||||||

HESCO

|

33944

|

4.44

|

27560

|

81.19

|

40199

|

4.16

|

31829

|

79.18

|

45714

|

4.51

|

35768

|

78.24

|

49009

|

4.91

|

35331

|

72.09

|

9.62

|

6.41

|

-3.21

|

SEPCO

|

33024

|

4.32

|

17708

|

53.62

|

33933

|

3.51

|

19875

|

58.57

|

36706

|

3.62

|

21222

|

57.82

|

36309

|

3.64

|

19923

|

54.87

|

2.40

|

2.99

|

0.59

|

SINDH

|

66968

|

8.76

|

45268

|

67.60

|

74132

|

7.67

|

51704

|

69.75

|

82420

|

8.13

|

56990

|

69.15

|

85318

|

8.55

|

55254

|

64.76

|

6.24

|

5.11

|

-1.13

|

Share %

|

8.76

|

6.32

|

|||||||||||||||||

Export to KESC

|

59026

|

7.72

|

84000

|

142.31

|

62409

|

6.46

|

60961

|

97.68

|

51572

|

5.09

|

36000

|

69.81

|

40639

|

4.07

|

38379

|

94.44

|

-8.91

|

-17.78

|

|

QESCO

|

36007

|

4.71

|

11461

|

31.83

|

44962

|

4.65

|

18968

|

42.19

|

65166

|

6.43

|

21223

|

32.57

|

55339

|

5.55

|

39640

|

71.63

|

11.34

|

36.37

|

25.03

|

Share %

|

4.71

|

1.60

|

4.65

|

2.19

|

6.43

|

2.37

|

5.55

|

4.21

|

|||||||||||

IPPS

|

833

|

0.11

|

826

|

99.16

|

640

|

0.07

|

792

|

123.75

|

619

|

0.06

|

629

|

101.62

|

993

|

0.10

|

987

|

99.40

|

4.49

|

4.55

|

|

Total

|

764842

|

716322

|

93.66

|

966230

|

866548

|

89.68

|

1013919

|

894137

|

88.19

|

997354

|

941926

|

94.44

|

6.86

|

7.08

|

0.22

|

||||

Collection figures for FYs

2017 shows further improvement in the recoveries position. Losses also have

registered an improvement. Losses are presented as follows:\

T&D LOSSES

|

||||

units for

|

units

|

units

|

units

|

|

Trans

|

billed

|

lost

|

lost

|

|

Year

|

M.kWh

|

M.kWh

|

M.kWh

|

%

|

2009

|

82702

|

62286

|

20416

|

24.69

|

2010

|

87115

|

68878

|

18237

|

20.93

|

2011

|

90575

|

71672

|

18903

|

20.87

|

2012

|

88987

|

71368

|

17619

|

19.80

|

2013

|

87080

|

70508

|

16572

|

19.03

|

2014

|

94089

|

76543

|

17546

|

18.65

|

2015

|

95979

|

78113

|

17866

|

18.61

|

2016

|

100871

|

81737

|

19134

|

18.97

|

Growth

|

2.88

|

3.96

|

-0.92

|

-3.69

|

The regulator allowed higher

losses in FY 2015 than in FY 2014, this

is presented as follow:

COMPARASION OF LOSSES in FY 2014 and FY 2015

|

|||||||||

Description

|

LESCO

|

GEPCO

|

FESCO

|

IESCO

|

MEPCO

|

HESCO

|

PESCO

|

SEPCO

|

Total

|

Allowed losses

|

|||||||||

FY 2016 %

|

11.75

|

9.98

|

9.50

|

9.39

|

15.00

|

20.50

|

26.00

|

27.50

|

15.23

|

Actual losses

|

|||||||||

FY 2016 %

|

13.94

|

10.58

|

10.24

|

9.09

|

16.45

|

26.46

|

33.76

|

37.87

|

17.95

|

Allowed losses

|

|||||||||

FY 2015 %

|

11.75

|

9.98

|

9.50

|

9.44

|

15.00

|

20.50

|

26.00

|

27.50

|

15.30

|

Actual losses

|

|||||||||

FY 2015 %

|

10.80

|

11.20

|

9.10

|

9.80

|

15.70

|

27.90

|

37.40

|

36.50

|

19.70

|

Allowed losses

|

|||||||||

FY 2014 %

|

9.01

|

9.98

|

9.50

|

9.45

|

15.00

|

15.00

|

20.00

|

20.00

|

13.05

|

actual % allowed

|

91.91

|

112.22

|

95.79

|

103.81

|

104.67

|

136.10

|

143.85

|

132.73

|

128.76

|

allowed 2015 % 2014

|

130.41

|

100.00

|

100.00

|

99.89

|

100.00

|

136.67

|

130.00

|

137.50

|

117.24

|

NEPRA issued the tariff determinations for FY 2014 for most of the DISCOs in January 2014. Allowed losses for DISCOs for 2013-14 were 13.02% compared to 18.7%. The 5.6% difference between determined loss and actual loss accumulated as CD of Rs 33.6 billion in FY 2014. The determinations for FY 2015 allowed 15.3% compared with expected losses of 18.70%, narrowing the gap between allowed and actual losses but will still result in accumulation of CD of Rs. 32 billion due to increase in generation. . For the purposes of this CD management plan, it was assumed that reductions in losses will reduce the flow of CD from Rs. 32 billion to

Rs. 11 billion Losses for FY 2017 have been reported to be 16.3%.

Surcharges:

Surcharges are levied under Section 31(5) of the Regulation of Electricity Generation, Transmission and Distribution Act 1997 (the NEPRA Act). Surcharges will be set at the level

that will rationalize subsidies and allow recovery of full cost of supply of electricity. This, however, will not completely

eliminate the subsidization of domestic sector by the industrial sector.

The impact of surcharges on

tariff determinations is illustrated by the following:

Variable charge FY 2016

to FY 2020 for B-3 Consumers. Rs./kWh

|

||||||||

LESCO

|

FESCO

|

MEPCO

|

GEPCO

|

IESCO

|

PESCO

|

HESCO

|

SEPCO

|

|

peak

|

13.85

|

14.55

|

14.50

|

15.80

|

14.30

|

15.70

|

15.45

|

19.60

|

off peak

|

6.85

|

6.25

|

6.80

|

9.50

|

6.70

|

9.65

|

9.25

|

12.75

|

Re-determined Tariff

|

||||||||

peak

|

14.87

|

14.48

|

13.32

|

15.22

|

14.85

|

18.90

|

18.49

|

20.56

|

off peak

|

7.97

|

6.51

|

7.32

|

8.42

|

7.05

|

13.05

|

12.50

|

14.31

|

Latest consumer tariff

|

||||||||

peak

|

16.04

|

16.23

|

16.37

|

15.36

|

16.63

|

19.82

|

21.96

|

22.45

|

off peak

|

9.16

|

8.26

|

10.37

|

8.56

|

9.03

|

13.97

|

16.06

|

16.20

|

Latest tariff 5 of

original tariff determined

|

||||||||

peak

|

15.81

|

11.55

|

12.90

|

-2.78

|

16.29

|

26.24

|

42.14

|

14.54

|

off peak

|

33.72

|

32.16

|

52.50

|

-9.89

|

34.78

|

44.77

|

73.62

|

27.06

|

The government is expected to increase the tariff by more than

Rs2 per unit with the addition of surcharges to make the tariff uniform for all

Discos because tariffs for SEPCO, HESCO and PESCO are very high. Although this

will significantly reduce the deficit

the inherent cross subsidization of domestic consumers by Industrial

consumers will not be mitigated. An analysis of tariffs on marginal cost basis

and on financial basis is presented as follows:

The Initial development

of LRMC has been made without the use of WASP simulation model. The capacity

LRMC at generation level is based on the assumption that the plant at the

margin will be an Open Cycle Gas Turbine (OCGT). The WAPDA System is evolving from an `energy

constrained’ system into a `demand constrained’ system. Un-served energy and

demand which was a result of failure to provide firm energy in the water dry

(winter) months is now occurring due to system inadequacies during high demand

periods. Periods of annual demand and daily demand will in future occur when

the system is at the maximum strain the least cost response to demand increment

can be summarized as follows:

. LRMC estimates are derives on

basis of: Capital cost of the plant at the margin, which is believed to be an

OCGT; Cost incurred due to enhanced un-served energy due to the fact that in

early plan periods Benefit in terms of energy cost savings due to advancement

of base load thermals and hydel plants in response to increase in demand and

consequent decrease in total energy cost. This results in the capacity marginal

cost at generation level to be about 90% the cost of an open cycle gas turbine.

LRMC estimates at an oil price of 52$ /bbl are as follows :

Table - : LRMC Estimates

|

|||

(Based on oil price of US$52)

|

|||

Voltage Level

|

Capacity

|

Peak Energy

|

Off Peak Energy

|

$/kW

|

c/kWh

|

c/kWh

|

|

Gen

|

417

|

10.24

|

6.39

|

500 kV

|

506

|

10.41

|

6.51

|

220 kV

|

540

|

10.59

|

6.58

|

132 kV

|

623

|

10.91

|

6.74

|

66 kV

|

718

|

11.23

|

7.00

|

11 kV

|

755

|

13.72

|

8.96

|

0.4 kV

|

970

|

16.35

|

10.25

|

Tariffs for a B-1

industrial consumer (load factor 0.4, coincidence 0.40),, a medium consumption

domestic consumer( load factor 0.35%, coincidence 0.95) and a higher

consumption commercial customer(load factor 0. 55, coincidence 1.0) is

presented as follows :

Tariff : Financial vs. Marginal

|

||||

Tariff Rs./kWh

|

||||

Customer

|

Financial

|

|||

Category

|

Financial

|

Marginal

|

% Marginal

|

|

Industry

|

13.46

|

11.59

|

16.19

|

|

Domestic

|

10.25

|

15.29

|

-32.98

|

|

Commercial

|

16.30

|

15.14

|

7.65

|

|

The above is based on

financial tariffs that are still under revision. The domestic customer is

subsidized by industrial customer. The high industrial tariff has repercussion

in industrial production and upon exports.

Privatization Receipts:

With the majority of DISCOs in the privatization plan of the GOP, the receipts

from privatization will be partially used to reduce/offset the stock of the PHCL debt and will reduce the need for budget to finance costs that cannot be met from other revenue sources. The CD management plan is thus dependent on the privatization of the DISCOs and GENCOs. There has been no progress on this

count. Government in recent moves has indicated bifurcation of four DISCOs to

make these more attractive to investors.

Low Collections by DISCOs from Private and Government

Consumers

Collections from private sector in most of the DISCOs have been

an issue which contributed to the buildup of CD. Actual recovery fluctuates

between 89-91% for the financial year 2015, whereas tariff determinations

assume 100%. Low collections have created a shortfall of Rs. 114 billion from

private consumers since the clearance of CD in July 2013. This less than 100%

collection is more pronounced in the five poorest performing DISCOs namely

PESCO, TESCO, HESCO, SEPCO and QESCO.

The plan was divided

into three parts. For all five distribution companies, recoveries will be

managed through power rationing. Experience in K-Electric has shown that this

kind of approach can improve collections significantly and quickly. For all

DISCOs, the aggregate technical and commercial losses (ATC) for each feeder

will be categorized by feeder into four: low (<10 and="" atc="" high="" medium="" very="">40% ATC). The second part of the

plan is to outsource to the private sector collections of bills in areas where

recoveries are weakest, based on the same categorization mentioned in the

preceding paragraph. This will build on experiences in K-Electric, LESCO, MEPCO

and PESCO areas.

The

third part will address collection of Federal and Provincial government bills.

For all Federal accounts, MOWP will notify DISCOs that non-payment beyond the

billing cycle of 45 days should result in disconnection, per commercial

procedures. MOWP will move a summary to the Council of Common Interests (CCI)

proposing more stringent requirements for Provincial departments. It will request CCI to approve 100%

deduction at source in the case of non-payment and disconnection for

non-payment beyond normal commercial terms. MOWP will require DISCOs to take

more rigorous action following disconnection, requiring prepayment for

electricity before reconnection is approved

The Government has already started action of collection from

private consumers including initiation of revenue based load shed mechanism

based on feeder wise AT&C losses. If the recovery is not affected, then the

recovery will be ensured through law enforcement agencies (NAB and FIA) and

incentive packages. The rationing system was introduced from August 1, 2015. Recoveries have in fact

shown an improvement , FY 2015 recoveries were

94.4% .

GENCO Heat Rates

Recent

moves by the regulator have allowed some relief. Adjustment on Account of Calorific Value (CV)

of fuel, GENCOs were directed, to maintain and submit, on quarterly basis, a detailed

record of consignment wise CV of the oil received

and consumed for power generation, for the adjustment on account of variation against the reference

CV, duly supported

with copies of test reports,

certified by fuel supplier:

and provision for part load operation. Allowed part-load adjustment by approving partial

loading curves for TPS Jamshoro

and TPS Muzaffargarh, and allowed the adjustment on account of partial loading,

if the units are partially loaded in instructions of system operator

(NPCC). In order to safeguard the interest of end-consumers, the Authority has decided to treat availability of GENCO power plants,

on similar lines as the IPPs. Therefore

it has directed the power purchaser not to pay capacity

charges to the GENCO power plants in case the power plant is not available as per PPA’s requirement.

Conclusions

The issue of financial non-viability of the power sector

structure has existed for a long time and is, historically, the result of poor

governance, delays in tariff determination and notification process, gap in

performance of DISCOs to achieve the targets set by regulator and prolonged

stays on fuel price adjustments (FPAs) granted by the courts. There are other

factors too which contribute to the continuous growth in the Circular Debt.

Successive governments have made efforts

to improve the power sector cash flows through various measures including

reducing litigations on FPA determination and notification process, improving

governance through re-constitution of Boards of Directors (BODs) with more

representation from private members, signing of performance contracts with BODs

and tariff rationalization. However, despite all the reforms, power sector cash

flows remained under pressure and resultantly delayed the payment to power

generators and fuel suppliers. Despite the clearance of Circular Debt through a

one-time Government grant of Rs 480 billion in 2013, the outstanding arrears to

power companies had once again climbed back up to reach Rs. 850 billion by May

2018.

The

accumulation of arrears towards power generators and fuel suppliers resulted in

less than optimal utilization of power plants and caused massive power deficit

in the country. For the first time in 2014, the Economic Coordination Committee

of Cabinet (ECC) defined the term “Circular Debt” as the amount of cash

shortfall in CPPA-G that it cannot pay to power supply companies. This

shortfall is the result of (a) the difference between the actual cost of

providing electricity in relation to revenues realized by the power

distribution companies (DISCOs) from sales to customers plus subsidies; and (b)

insufficient payments by the DISCOs to CPPA out of realized revenue as they

give priority to their own cash flow needs. This revenue shortfall cascades

through the entire energy supply chain, from electricity generators to fuel

suppliers, refiners, and producers; resulting in a shortage of fuel supply to

the public sector thermal generating companies (GENCOs), a reduction in power

generated by Independent Power Producers (IPPs), and an increase in load

shedding. Table below briefly lists some of the reasons for

accumulation of Circular Debt and recommendations for addressing them.

Table: Proposed Solutions for

Reducing/Eliminating Circular Debt (CD)

Issue

|

Recommendation

|

Rationale

|

Lingering

Tariff Dispute with GOAJK

|

· In order to stop the

accumulation of receivables in future, the Tariff for GoAJK should be

determined as Rs. 5.79 / KWh as agreed by AJK and the same may be notified by

GOP.

· Modalities to be finalized

between Ministry of Finance and Ministry of Energy for settlement of

outstanding receivables

|

To

reduce the CD accumulation

|

Non-Settlement

of Issues with FBR and blockage of refunds

|

· Recovery of blocked refunds

from FBR and out of court settlement of all the disputes with FBR.

· Zero Rating for Power Sector

to stop the blockage of refunds in future

|

To

improve financial viability of DISCOs and payments towards CPPA

|

Delay

in Tariff Notification

|

· Notification of pending

determined tariff Including Multiyear Tariff

|

To

ensure recovery of tariff from either consumer or through subsidy as per

determined cost

|

Line

Losses & Recovery difference with NEPRA Target

|

· Review of targets by

Regulator

· DISCOs to take necessary

measures to control the line losses and improve recovery

|

To

reduce the CD accumulation

|

Receivables Issues related to FATA

&

Baluchistan Tube Wells

|

· Policy measures planned in

2015 to be implemented

· Ministry of Finance to

allocate sufficient subsidy budgets for FATA & Baluchistan Tube wells to

stop the flow.

|

To

reduce the CD accumulation

|

Other

needed measures

· Implementation of at-source

deduction mechanism for recovery from Government Departments as per CCI

decision

·

Implementation of Cost of Service based Tariff to eliminate

cross subsidies

·

Improvement

in the overall generation mix by inducting less costly power plants

· Improving governance leading to

phase wise privatization of all DISCOs & GENCOs

Update: Jan., 2, 2019: The Ministry of Power Division on Tuesday

informed the Public Accounts Committee (PAC) that the amount of circular debt

had reached Rs755 billion

Power Division has submitted the following

recommendations in order to resolve the long outstanding issues: (i) Nepra's

determined tariff for 1-100 unit slab of domestic category will be applicable

for AJ&K from January 1, 2018, currently which is Rs 5.79/kWh. Difference

between bulk supply tariff and 1-100 unit tariff will be provided by Finance

Division. The arrangement will continue till next Nepra tariff determination of

2018-19; (ii) bulk power supply to AJ&K may be made from CPPA-G as is being

done in case of K-Electric as per tariff determination by Nepra; (iii) Finance

Division may provide sufficient budget for AJ&K electricity bill.

Appropriate provisioning in AJ&K budget will eliminate any financial built

up or need for electricity subsidy for AJ&K and; (iv) Finance Division may

frame a mechanism for clearing the stock of dues which have piled up from 2011

onwards.

Update:

Jan., 5, 2019: circular debt has now crossed about Rs1.4tr. In August 2018,

this would mean that the circular debt has climbed by more than Rs200bn in the

137 days since August 2018. For

perspective, consider that the same figure stood at Rs922bn at the end of

November 2017, meaning that the size of the debt increased faster from August

till today than it did in the preceding ten months. At the moment, increasing

quantities of power sector inefficiencies are being passed onto the consumer

through miscellaneous surcharges and an elevated target for losses allowed by

NEPRA. The power sector is crying out for proper leadership, and the costs of

inaction are rising by the day.

Circular Debt; May, 7,

2019: Circular

debt, which increased by Rs450 billion during 2017-18, would be eliminated by

next year; Prime Minister was informed on Monday. Circular debt, caused by debt

piled up due to electricity leakages, theft and low recovery of bills from many

state-owned offices, schools, police stations, mosques, monuments and others,

has crossed the Rs1.4 trillion mark. The meeting was informed that circular

debt would be brought down to Rs293 billion during the current year and to Rs96

billion by 2019-20. It was told that the ministry’s drive to curb power theft

and recovery of dues had brought in positive outcomes. Within four months, the

additional power dues worth Rs48 billion had been recovered that would touch

Rs80 billion mark by year end and Rs190 billion till June 2020. The prime

minister was told that the special focus given to handling the losses caused by

theft, technical and transmission issues was coming to fruition. As a step to

curb power theft, 27,000 first information reports (FIR) had been registered

against those involved, while 4,225 people had been arrested including 433

officials of the power sector. Moreover, another 1,467 officials had been

charge-sheeted.

Circular Debt: Tube well conversion to Solar: May, 10, 2019: The Baluchistan government has decided to switch

tube-wells installed in the fields in the province to the solar system.

There are around 29,000 agriculture tube-wells running on electricity across

the province. It was decided that the geo-testing mechanism will be adopted for

the verification of tube-wells.

Circular debt retirement; July, 30, 2019: The government will be raising about Rs200bn through Islamic

bonds next month to reduce circular debt after securing about Rs11bn relief

from independent power producers (IPPs )

The government has now finalised those negotiations under which

the 10 IPPs, which had won international arbitration against the government,

have agreed to reduce their mark-up payments on overdue arrears from Kibor plus

4.5 per cent to Kibor plus 2pc. They have also agreed to apply mark-up after 90

days of non-payment instead of the existing 35 days, while the mark-up will now

be payable on the outstanding amount once instead of compound interest rate. As

a result, the government is estimated to get a financial relief of about Rs11bn

against the original cost of about Rs34bn awarded in favor of the IPPs by the

LCIA. The two sides are expected to sign the settlement agreement over the next

couple of weeks.

Power division had started

negotiations with the 10 IPPs set up under the 2002 power policy for

out-of-court settlement of originally Rs16bn award allowed by the LCIA. The

arbitration cost had increased to Rs34bn on account of interests and other

costs. An official in one of the IPPs said the government might be

overestimating the relief because the negotiations were limited to the extent

of interest payments. It might be a couple of billions of rupees and nothing

like Rs11bn, he said, adding that the out-of-court settlement would be a time-bound

discount and in case of non-clearance of dues within 45 days, the original

mark-up would get revived.

Simultaneously, officials are expecting that Rs200bn Sukuk

financing will also be approved by the Economic Coordination Committee (ECC) of

the cabinet later this week to ensure timely clearance of not only the

arbitration liability to the litigants but also other outstanding dues to all

the IPPs and fuel suppliers suffering cash flow problems because of around

Rs1.4 trillion circular debt.

An official said the ECC had approved in principle up to Rs400bn

Islamic financing for the power sector in February this year in two phases, but

a fresh approval by the ECC as well as the cabinet was required for the second

tranche because of changed financing costs arising out of more than 500 basis

points increase in the central bank’s policy rate to 13.25pc under the IMF

programme. Pakistan.

The assets belonging to a number of public sector power companies

have been mortgaged in favour of the financiers as well as the previous bond

backed by a government guarantee with a 10-year maturity at a rental return of

Kibor plus 80 basis points. The bonds entail half-yearly rental repayments from

the date of draw-down and repayments are made directly by the central bank on

the basis of a budgetary allocation by the finance ministry on its standing

instructions to direct debit for return and maturity repayment at the SBP

counter.

The boards of directors of all power distribution and generation

companies have agreed to pledge the properties/assets in the trust for banks.

Some additional properties and assets have been selected in the distribution

and generation network as collateral against rental payments.

At present the National Electric Power Regulatory Authority,

National Accountability Bureau and newly created Inquiry Commission on Debt are

probing the IPPs financials for purported higher than normal profits. The

government is also considering appointing a specialized commission comprising

international engineering, legal and financial experts on the issue.

Losses decreased: Aug., 12, 2019: The power sector has achieved in its revenues

a record increase of over Rs121 billion while curtailing line losses worth

Rs16bn, or 1.4 per cent.The initiatives include

both administrative and technical measures pertaining to system augmentation

and upgradation. Under the campaign to curb electricity theft, Rs1,368 million

was recovered from 5,318 power thieves after registering 36,000 FIRs against

them. The Aerial Bundled Cable is another project to

control and pre-empt illegal connections through direct hooking, thereby

controlling the menace of kundas and reducing line losses in high-loss areas.

The Peshawar Electric Supply Company and Sukkur Electric Supply Company have

already started installation of these cables as and where they clear feeders in

their anti-theft campaign. The anti-corruption and anti-theft drive has shown

positive effects on recovery of outstanding dues as well. It has motivated the

consumers to pay the bills in time. Discos’ recovery has shown an improvement

of 1pc since the launch of the campaign.

The electricity generation in FY19 grew barely 1 percent year-on-year to 122 billion units, which translates into 103 billion units of actual consumption, after factoring in the system losses. The losses have continued to be high, close to 20 percent, and in cases of some discos, even higher than easier thresholds. The regulator's inability to have a tighter control and instead allowing far more than threshold losses as part of final tariffs, has been a massive problem, and there was no progress on this front.

Nonetheless, the improvement did come in FY19 as the share of furnace oil based generation was reduced to single digits, while that of imported LNG and coal based generation reached new highs.

It would have been much nicer, had the benefit of a much improved generation mix been transferred to the consumers. But in fact the tariffs kept on increasing as Pakistan entered yet another IMF programme. The tariff increase was made a structural benchmark, in order to reduce the cost differential and put a lid on the ballooning circular debt, which had crossed Rs 1 trillion.

The tariffs have been increased across user categories, barring domestic consumers using up to 300 units a month. This in itself is more of a problem, as nearly 80 percent of domestic power consumption is exempt from tariff increase, and the allocated subsidy of nearly Rs150 billion in the budget, does not cover up for the same.

The rise of unfunded subsidy has been a major problem, and the issue exacerbated with the government's relief scheme for industrial users in general and export industries in particular. That takes out another 25 percent of total power consumption out of the tariff hike, instead this requires room for more subsidies, which have not been allocated. Either the government will have to roll back some of it, or will end up running higher subsidies, or in case of delayed payments, another round of circular debt may well be in the offing.

the capacity payments. Not that the government is not looking to recover the difference between price and cost, but there is little debate on the elephant in the room, that is the capacity payment component. The amount of upwards adjustment that may be required for FY19 determinations for respective discos, could be too hot to handle. The IMF is not the worry as far as the power prices are concerned, capacity payments are.

The capacity payments in FY16 were Rs280 billion or Rs3.4 per unit sold. This increased to Rs644 billion or Rs6.2 per unit in FY18, constituting almost 60 percent of the power purchase price

The

distribution companies (Discos) are facing revenue shortfalls. In 2018-19,

about 93,887 million units worth Rs1.342 trillion were billed to consumers

against which recovery of Rs1.061tr was made indicating a recovery percentage

of 79.06pc.

The

shortfall resulted in less receipt of revenue by the Discos, showing `managerial

inefficiencies and policy bottlenecks constraining the Central Power Purchasing

Agency (CPPA) to pay-off its energy procurement liabilities.

Compared with the last financial year, there was an improvement of 1pc in revenue recovery. Still, the recovery shortfall of 21pc posed a significant operational challenge for Discos. Recovery in Hyderabad, Tribal, Quetta and Sukkur companies was 54.17pc, 18.92pc, 24.29pc and 38.54pc respectively only in 2018-19.

Compared with the last financial year, there was an improvement of 1pc in revenue recovery. Still, the recovery shortfall of 21pc posed a significant operational challenge for Discos. Recovery in Hyderabad, Tribal, Quetta and Sukkur companies was 54.17pc, 18.92pc, 24.29pc and 38.54pc respectively only in 2018-19.

Losses

beyond the limit set by Nepra meant financial losses for the company as well as

a cyclic increase in the CPPA receivable amounts pertaining to Discos.

The rest of T&D losses in Discos and the financial impact thereof amounted to Rs37.5bn and Rs35.8bn in 2017-18 and 2018-19.

This implies that the performance of Discos in reducing T&D losses remained unsatisfactory. Moreover, it also shows that the development initiatives being made in these companies for enhancing the power transmission and distribution system are yet to make any appreciable impact.

Huge receivables from running and dead defaulters remained another major challenge. Over the years the volume of receivables from running and dead energy defaulters have increased significantly and it has become an important cause for power sector debt accumulation. As of June 2019, the total receivables from running and dead defaulters amounted to Rs572.179bn. Of this, Rs476.932bn pertained to running defaulters and Rs95.247bn to dead defaulters. Such a huge amount of receivables has added to the financial crunch in the power sector that demands immediate consideration and intervention.

Due to late payment of government subsidies like tariff differential subsidy, agricultural subsidy for tubewells, other provincial government subsidies, subsidy to Azad Jammu and Kashmir government and outstanding payments from K-Electric, Rs.549.2bn were held up as of June 2019. These receivables are adding up into the overall circular debt of the power sector. As on June 30, 2019, the total amount of circular debt stood at Rs.1.517tr including Power Holding Private Limited loans of Rs809.840bn from Rs1.160tr in 201718, registering an increase of Rs357.378bn or 31pc in the one financial year.

The rest of T&D losses in Discos and the financial impact thereof amounted to Rs37.5bn and Rs35.8bn in 2017-18 and 2018-19.

This implies that the performance of Discos in reducing T&D losses remained unsatisfactory. Moreover, it also shows that the development initiatives being made in these companies for enhancing the power transmission and distribution system are yet to make any appreciable impact.

Huge receivables from running and dead defaulters remained another major challenge. Over the years the volume of receivables from running and dead energy defaulters have increased significantly and it has become an important cause for power sector debt accumulation. As of June 2019, the total receivables from running and dead defaulters amounted to Rs572.179bn. Of this, Rs476.932bn pertained to running defaulters and Rs95.247bn to dead defaulters. Such a huge amount of receivables has added to the financial crunch in the power sector that demands immediate consideration and intervention.

Due to late payment of government subsidies like tariff differential subsidy, agricultural subsidy for tubewells, other provincial government subsidies, subsidy to Azad Jammu and Kashmir government and outstanding payments from K-Electric, Rs.549.2bn were held up as of June 2019. These receivables are adding up into the overall circular debt of the power sector. As on June 30, 2019, the total amount of circular debt stood at Rs.1.517tr including Power Holding Private Limited loans of Rs809.840bn from Rs1.160tr in 201718, registering an increase of Rs357.378bn or 31pc in the one financial year.

The electricity generation in FY19 grew barely 1 percent year-on-year to 122 billion units, which translates into 103 billion units of actual consumption, after factoring in the system losses. The losses have continued to be high, close to 20 percent, and in cases of some discos, even higher than easier thresholds. The regulator's inability to have a tighter control and instead allowing far more than threshold losses as part of final tariffs, has been a massive problem, and there was no progress on this front.

Nonetheless, the improvement did come in FY19 as the share of furnace oil based generation was reduced to single digits, while that of imported LNG and coal based generation reached new highs.

It would have been much nicer, had the benefit of a much improved generation mix been transferred to the consumers. But in fact the tariffs kept on increasing as Pakistan entered yet another IMF programme. The tariff increase was made a structural benchmark, in order to reduce the cost differential and put a lid on the ballooning circular debt, which had crossed Rs 1 trillion.

The tariffs have been increased across user categories, barring domestic consumers using up to 300 units a month. This in itself is more of a problem, as nearly 80 percent of domestic power consumption is exempt from tariff increase, and the allocated subsidy of nearly Rs150 billion in the budget, does not cover up for the same.

The rise of unfunded subsidy has been a major problem, and the issue exacerbated with the government's relief scheme for industrial users in general and export industries in particular. That takes out another 25 percent of total power consumption out of the tariff hike, instead this requires room for more subsidies, which have not been allocated. Either the government will have to roll back some of it, or will end up running higher subsidies, or in case of delayed payments, another round of circular debt may well be in the offing.

the capacity payments. Not that the government is not looking to recover the difference between price and cost, but there is little debate on the elephant in the room, that is the capacity payment component. The amount of upwards adjustment that may be required for FY19 determinations for respective discos, could be too hot to handle. The IMF is not the worry as far as the power prices are concerned, capacity payments are.

The capacity payments in FY16 were Rs280 billion or Rs3.4 per unit sold. This increased to Rs644 billion or Rs6.2 per unit in FY18, constituting almost 60 percent of the power purchase price

The

dependable generation capacity in FY19 went up by almost 20 percent

year-on-year to 31000 MW. The demand did not grow. The RLNG plants are fully

available, among many others from the CPEC projects. No demand growth and

higher generation availability, with contracts based on take-or-pay, it is

estimated that the capacity payments component for FY19 would be north of Rs900

billion. The currency devaluation has also played its role.

Now with almost Rs9 per unit as capacity payment, it is obvious that the benefit of lower fuel price and improved generation mix was never going to materialize. And there is more to come in lieu of tariff adjustments. The latest IMF programme, like any other IMF programme, is overly focused on price as the key to reforms. Yes, price is an integral part of the power sector reforms, but it is surely not the only one. It did not work back then, it will not work now. The government is due to announce the revised tariffs for FY19 by September end, as per the IMF's structural benchmark. And the budgeted subsidy may not be enough to cater for the increase.

The governance reform, the focus on transmission, privatization of DISCOs and commercially opening up the market are all key component of the reform, which have sadly taken a backseat, as price becomes the focus. The first year was a missed opportunity; the second could be a disaster, if they don't look beyond pricing as means of reforms.

Now with almost Rs9 per unit as capacity payment, it is obvious that the benefit of lower fuel price and improved generation mix was never going to materialize. And there is more to come in lieu of tariff adjustments. The latest IMF programme, like any other IMF programme, is overly focused on price as the key to reforms. Yes, price is an integral part of the power sector reforms, but it is surely not the only one. It did not work back then, it will not work now. The government is due to announce the revised tariffs for FY19 by September end, as per the IMF's structural benchmark. And the budgeted subsidy may not be enough to cater for the increase.

The governance reform, the focus on transmission, privatization of DISCOs and commercially opening up the market are all key component of the reform, which have sadly taken a backseat, as price becomes the focus. The first year was a missed opportunity; the second could be a disaster, if they don't look beyond pricing as means of reforms.