Confucianism (R122)

Introduction

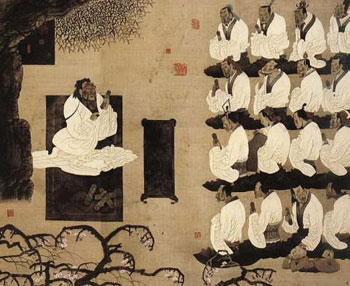

The philosophy of Confucius, also

known as Confucianism, emphasized personal and

governmental morality, correctness of social relationships, justice and sincerity.

His followers competed successfully with many other schools during the Hundred Schools of Thought era only to be suppressed in favor of the Legalists during the Qin dynasty. Following the victory of Han over Chu after the collapse of Qin, Confucius's thoughts received

official sanction and were further developed into a system known in the West as

Neo-Confucianism, and later New Confucianism (Modern Neo-Confucianism). Confucius is traditionally credited with having

authored or edited many of the Chinese

classic texts including all of the Five

Classics, but modern scholars are cautious of attributing specific assertions to

Confucius himself. Aphorisms concerning his teachings were compiled in the Analects, but

only many years after his death.

Confucius presented himself as a ‘transmitter who invented nothing’, because he

believed he was teaching the natural path to good behavior passed down from

older, divine masters. Around the second century B.C., Confucius’s works were

collected into the Analects (Lunyu), a collection of sayings written down by

his followers. These are not always commandments, because Confucius didn’t like

prescribing strict rules. Instead, he believed that if he simply lived

virtuously, he would inspire others to do the same.

Summary

Confucius's principles have commonality with

Chinese tradition and belief. He championed strong family loyalty, ancestor veneration, and

respect of elders by their children and of husbands by their wives,

recommending family as a basis for ideal government. He espoused the well-known

principle "Do not do unto others what you do not want done to

yourself", the Golden Rule. He is also a traditional deity in Daoism.

Confucius is widely considered as one of the most important and influential

individuals in shaping human history. His teaching and philosophy greatly

impacted people around the world and remains influential today. Confucianism pays particular

emphasis on the importance of the family and social harmony, rather than on an

otherworldly soteriology,[ the core of Confucianism is humanistic.[ According

to the Herbert Fingarette's concept of "the secular as sacred",

Confucianism regards the ordinary activities of human life — and especially in

human relationships as a manifestation of the sacred, because they are the

expression of our moral nature , which has a transcendent anchorage in Heaven

and a proper respect of the gods . The-worldly concern of Confucianism rests on

the belief that human beings are fundamentally good, and teachable, improvable,

and perfectible through personal and communal endeavor especially

self-cultivation and self-creation. Confucian thought focuses on the

cultivation of virtue and maintenance of ethics. Some of the basic Confucian

ethical concepts and practices include humaneness, it is said to be the essence

of the human being which manifests as compassion, and it is the virtue-form of

Heaven. It includes: the upholding of righteousness and the moral disposition

to do good; a system of ritual norms and propriety that determines how a person

should properly act in everyday life according to the law of Heaven; the

ability to see what is right and fair, or the converse, in the behaviors

exhibited by others. Confucianism holds one in contempt, either passively or

actively, for failure to uphold the cardinal moral values described above.

Confucius

and religion

Confucius is almost unique amongst eastern philosophers who did

not claim to present the unseen world to followers. He does not mention God and

does not address the question of immortality. When asked he said “if you cannot

even know men, how can you we know spirits”. Yet his teachings had a profound impact

on countless Chinese people, he is revered in China and elsewhere .He provided

answers related to common relations of life. He believed that virtue was based

on knowledge, knowledge of man’s own heart and knowledge of human kind. He

presented no ideas related to life after death.

Life

Confucius, was born in 551 BC, his father was governor of Shuntang

he married at eighteen and was employed in a minor position in government At his twenty fourth year he entered in to a

three years mourning for his mothers demise (such temporary withdrawal is

common to all philosophers, thinkers and religious leaders).His seclusion led

him to study of the then present condition of his country and vowed to resolve

the malaise in the Chinese society. By the time he was thirty he was regarded

as a thinker, a great Teacher and disciples flocked to him. In spite of his fame he kept working in the

government position, until he became Chief Judge in his county of Lu. His

tenure as Judge put an end to crime in the country and he became the idol of

people. The feudal Lords were alarmed by his fame and his achievements and

drove him away from home; he wandered around with his few disciples until he

was sixty nine years old .when he returned to his home state. He died at the

age of seventy three in 478 BC.

In the Analects, Confucius presents himself as a "transmitter

who invented nothing". He puts the greatest emphasis on the importance of

study, and it is the Chinese

character for study that opens the text.

Far from trying to build a systematic or formalist theory, he wanted his disciples to master and

internalize older classics, so that their deep thought and thorough study would

allow them to relate the moral problems of the present to past political events

(as recorded in the Annals) or

the past expressions of commoners' feelings and noblemen's reflections (as in

the poems of the Book of Odes).

The Analects are

a long and seemingly disorganized book of short events, filled with strange

conversations between Confucius and his disciples, like this one:

‘Tsze-kung wished to do away

with the offering of a sheep connected with the inauguration of the first day

of each month.

The Master said, ‘Tsze, you

love the sheep; I love the ceremony’.

At first this is baffling, if

not also humorous. But Confucius is reminding Tsze—and us—about the importance

of ceremony.

In the modern world we tend to

shun ceremony and see this as a good thing—a sign of intimacy, or a lack of

pretension. Many of us seek informality and would like nothing more than to be

told ‘just make yourself at home!’ when visiting a friend. But Confucius

insisted on the importance of rituals. The reason he loved ceremonies more than

sheep is that he believed in the value of li: etiquette, tradition, and ritual.

This might seem very outdated

and conservative at first glance. But in fact, many of us long for particular

rituals—that meals mum cooked for us whenever we were sick, for example, or the

yearly birthday outing, or our wedding vows. We understand that certain

premeditated, deliberate, and precise gestures stir our emotions deeply.

Rituals make our intentions clear, and they help us understand how to behave.

Confucius taught that a person who combines compassion (‘ren’) and rituals

(‘li’) correctly is a ‘superior man’, virtuous and morally powerful.

We should treat our parents

with reverence

Confucius had very strict ideas

about how we should behave towards our parents. He believed that we should obey

them when we are young, care for them when they are old, mourn at length when

they die and make sacrifices in their memory thereafter. ‘In serving his

parents, a son may remonstrate with them, but gently’, he said. ‘When he sees

that they do not incline to follow his advice, he shows an increased degree of

reverence, but does not abandon his purpose; and should they punish him, he

does not allow himself to murmur’. He even said that we should not travel far

away while our parents are alive and should cover for their crimes. This

attitude is known as filial piety (‘xiào’). This

sounds strange in the modern age, when many of us leave our parents’ homes as

teenagers and rarely return to visit. We may even see them as strangers,

arbitrarily thrust upon us by fate. After all, our parents are so out of touch,

so pitifully human in their shortcomings, so difficult, so judgmental—and they

have such bad taste in music! Yet Confucius recognised that in many ways moral

life begins in the family. We cannot truly be caring, wise, grateful and

conscientious unless we remember Mum’s birthday and meet Dad for lunch.

We should be obedient to honorable

people

Modern society is very

egalitarian. We believe that we’re born equal, each uniquely special, and

should ultimately be able to say and do what we like. We reject many rigid,

hierarchical roles. Yet Confucius told his followers, ‘Let the ruler be a

ruler, the subject a subject, a father a father, and a son a son’.

This might sound jarring, but

it is in fact important to realise that there are people worth our deep

veneration, even our simple and humble obedience. We need to be modest enough

to recognise the people whose experience or accomplishments outweigh our own.

We also should practice peaceably doing what these people need, ask, or

command. Confucius explained, ‘The relation between superiors and inferiors is

like that between the wind and the grass. The grass must bend, when the wind

blows across it.’ Bending gracefully is, in fact, not a sign of weakness but a

gesture of humility and respect.

Cultivated knowledge can be

more important than creativity

Modern culture places a lot of

emphasis on creativity – unique insights that come to us suddenly. But

Confucius was adamant about the importance of the universal wisdom that comes

from years of hard work and reflection. He listed the aforementioned compassion

(‘ren’) and ritual propriety (‘li’) among three other virtues: justice (‘yi’),

knowledge (‘zhi’) and integrity (‘xin’). These were known as the ‘Five Constant

Virtues’. While Confucius believed that people were inherently good, he also

saw that virtues like these must be constantly cultivated just like plants in a

garden. He told his followers, ‘At fifteen, I had my mind bent on learning. At

thirty, I stood firm. At forty, I had no doubts. At fifty, I knew the decrees

of Heaven. At sixty, my ear was an obedient organ for the reception of truth. At

seventy, I could follow what my heart desired, without transgressing what was

right.’ He spoke about moral character and wisdom as the work of a lifetime.

(We can see now why he had such reverence for his elders!) Of

course, a burst of inspiration may well be what we need to start our business

or redo our rough draft or even reinvent our life. But if we’re being very

honest with ourselves, we’ll have to admit that we also need to devote more

energy to slowly changing our habits. This, more than anything else, is what

prevents us from becoming truly intelligent, accomplished, and wise.

The Doctrine of the Mean

What Heaven has conferred is called The Nature; accordance with this nature is called The Path of duty; the regulation of

this path is called Instruction. The path may not be left for an instant.

If it could be left, it would not be the path. The way which the superior man

pursues, reaches wide and far, and yet is secret. Common men and women, however ignorant, may intermeddle with the knowledge of it; yet in its utmost reaches, there is that which even the sage

does not know. The superior man does what is proper to the station in which he is; he does not desire to go beyond this. In

archery we have something like the way of the superior man. When the archer

misses the center of the target, he turns round and seeks for the cause of his failure in himself. His presenting himself with his institutions before spiritual beings, without any doubts arising about them, shows that he knows Heaven. His being prepared, without any misgivings, to wait for the

rise of a sage a hundred ages after, shows that he knows men. All things are nourished

together without their injuring one another. It is only he who is

possessed of the most complete sincerity that can exist under heaven, who can give its full development to his nature. Able to give its full development to his own nature, he can do the same to

the nature of other men.

It is the way of the superior man to prefer

the concealment of his virtue, while it daily becomes more illustrious,

and it is the way of the mean man to seek notoriety, while he daily goes more and more to ruin. The superior man examines his heart, that there may be nothing wrong there, and that he may have no cause for dissatisfaction with himself.

That wherein the superior man cannot be equaled is simply this — his work which

other men cannot see.

It is said in the Book of

Poetry, "In silence is the offering presented, and the spirit approached to; there is not the slightest contention." Therefore

the superior man does not use rewards, and the people are stimulated to virtue. He does not show anger, and the

people are awed more than by hatchets and battle-axes.

·

What Heaven has conferred is called The Nature; an accordance with this

nature is called The Path of duty; the regulation of this path is called

Instruction. The path may not be left for an instant. If it could be left, it

would not be the path. On this

account, the superior man does not wait till he sees things, to be cautious,

nor till he hears things, to be apprehensive.

·

There is

nothing more visible than what is secret, and nothing more manifest than what

is minute. Therefore the superior man is watchful over himself, when he is

alone.

·

Let the states of equilibrium and harmony exist in perfection, and a

happy order will prevail throughout heaven and earth, and all things will be

nourished and flourish.

·

Perfect is

the virtue which is according to the Mean! Rare have they long been among the

people, who could practice it!

·

I know how it

is that the path of the Mean is not walked in — The knowing go beyond it, and

the stupid do not come up to it. I know how it is that the path of the Mean is

not understood — The men of talents and virtue go beyond it, and the worthless

do not come up to it.

·

There is no

body but eats and drinks. But they are few who can distinguish flavors.

·

Men all say,

"We are wise"; but being driven forward and taken in a net, a trap,

or a pitfall, they know not how to escape. Men all say, "We are

wise"; but happening to choose the course of the Mean, they are not able

to keep it for a round month.

·

The kingdom,

its states, and its families, may be perfectly ruled; dignities and emoluments

may be declined; naked weapons may be trampled under the feet; but the course

of the Mean cannot be attained to.

·

To show forbearance and gentleness in teaching others; and not to revenge

unreasonable conduct — this is the energy of southern regions, and the good man

makes it his study. To lie under arms; and meet death without regret — this is

the energy of northern regions, and the forceful make it their study.

Therefore, the superior man cultivates a friendly harmony, without being weak —

How firm is he in his energy! He

stands erect in the middle, without inclining to either side — How firm is he

in his energy! When good principles prevail in the government of his country,

he does not change from what he was in retirement. How firm is he in his

energy! When bad principles prevail in the country, he maintains his course to

death without changing — How firm is he in his energy!

·

The superior

man accords with the course of the Mean. Though he may be all unknown, unregarded

by the world, he feels no regret — It is only the sage who is able for this.

·

The way which the superior man pursues, reaches wide and far, and yet is

secret. Common men and women, however ignorant, may intermeddle with the

knowledge of it; yet in its utmost reaches, there is that which even the sage

does not know. Common men and

women, however much below the ordinary standard of character, can carry it into

practice; yet in its utmost reaches, there is that which even the sage is not

able to carry into practice. Great

as heaven and earth are, men still find some things in them with which to be

dissatisfied. Thus it is that, were the superior man to speak of his way in all

its greatness, nothing in the world would be found able to embrace it, and were

he to speak of it in its minuteness, nothing in the world would be found able

to split it.

·

The way of

the superior man may be found, in its simple elements, in the intercourse of

common men and women; but in its utmost reaches, it shines brightly through Heaven

and Earth.

·

The Path is

not far from man. When men try to pursue a course, which is far from the common

indications of consciousness, this course cannot be considered The Path.

·

The superior man governs men, according to their nature, with what is

proper to them, and as soon as they change what is wrong, he stops.

·

When one cultivates to the utmost the principles of his nature, and

exercises them on the principle of reciprocity, he is not far from the path.

What you do not like when done to yourself, do not do to others.

·

Earnest in

practicing the ordinary virtues, and careful in speaking about them, if, in his

practice, he has anything defective, the superior man dares not but exert

himself; and if, in his words, he has any excess, he dares not allow himself

such license. Thus his words have

respect to his actions, and his actions have respect to his words; is it not

just an entire sincerity which marks the superior man?

·

The superior man does what is proper to the station in which he is; he

does not desire to go beyond this. In a position of wealth and honor, he does

what is proper to a position of wealth and honor. In a poor and low position,

he does what is proper to a poor and low position. Situated among barbarous tribes, he does

what is proper to a situation among barbarous tribes. In a position of sorrow

and difficulty, he does what is proper to a position of sorrow and difficulty.

The superior man can find himself in no situation in which he is not

himself. In a high situation, he

does not treat with contempt his inferiors. In a low situation, he does not

court the favor of his superiors. He rectifies himself, and seeks for

nothing from others, so that he has no dissatisfactions. He does not murmur

against Heaven, nor grumble against men. Thus it is that the superior man is quiet and calm, waiting for the

appointments of Heaven, while the mean man walks in dangerous paths, looking

for lucky occurrences.

·

In archery we have something like the way of the superior man. When the

archer misses the center of the target, he turns round and seeks for the cause

of his failure in himself.

·

The way of

the superior man may be compared to what takes place in traveling, when to go

to a distance we must first traverse the space that is near, and in ascending a

height, when we must begin from the lower ground.

·

How

abundantly do spiritual beings display the powers that belong to them! We look

for them, but do not see them; we listen to, but do not hear them; yet they

enter into all things, and there is nothing without them.

·

Heaven, in the production of things, is sure to be bountiful to them,

according to their qualities. Hence the tree that is flourishing, it nourishes,

while that which is ready to fall, it overthrows.

·

The administration of government lies in getting proper men. Such men are

to be got by means of the ruler's own character. That character is to be

cultivated by his treading in the ways of duty. And the treading those ways of

duty is to be cultivated by the cherishing of benevolence.

·

Benevolence is the characteristic element of humanity.

·

To be fond of

learning is to be near to knowledge. To practice with vigor is to be near to

magnanimity. To possess the feeling of shame is to be near to energy.

·

By the

ruler's cultivation of his own character, the duties of universal obligation

are set forth. By honoring men of virtue and talents, he is preserved from

errors of judgment.

·

In all things success depends on previous preparation, and without such

previous preparation there is sure to be failure. If what is to be spoken be previously determined, there will be no

stumbling. If affairs be previously determined, there will be no difficulty

with them. If one's actions have been previously determined, there will be no

sorrow in connection with them. If principles of conduct have been previously

determined, the practice of them will be inexhaustible.

·

Sincerity is the way of Heaven. The attainment of sincerity is the way of

men. He who possesses

sincerity is he who, without an effort, hits what is right, and apprehends,

without the exercise of thought — he is the sage who naturally and easily

embodies the right way. He who attains to sincerity is he who chooses what is

good, and firmly holds it fast. To this attainment there are requisite the

extensive study of what is good, accurate inquiry about it, careful reflection

on it, the clear discrimination of it, and the earnest practice of it.

·

The superior

man, while there is anything he has not studied, or while in what he has

studied there is anything he cannot understand, Will not intermit his labor.

While there is anything he has not inquired about, or anything in what he has

inquired about which he does not know, he will not intermit his labor. While

there is anything which he has not reflected on, or anything in what he has

reflected on which he does not apprehend, he will not intermit his labor. While

there is anything which he has not discriminated or his discrimination is not

clear, he will not intermit his labor. If there be anything which he has not

practiced, or his practice fails in earnestness, he will not intermit his

labor. If another man succeed by one effort, he will use a hundred efforts. If

another man succeed by ten efforts, he will use a thousand. Let a man proceed

in this way, and, though dull, he will surely become intelligent; though weak,

he will surely become strong.

·

When we have intelligence resulting from sincerity, this condition is to

be ascribed to nature; when we have sincerity resulting from intelligence, this

condition is to be ascribed to instruction. But given the sincerity, and there

shall be the intelligence; given the intelligence, and there shall be the

sincerity.

·

It is only he who is possessed of the most complete sincerity that can

exist under heaven, who can give its full development to his nature. Able to

give its full development to his own nature, he can do the same to the nature

of other men. Able to give its

full development to the nature of other men, he can give their full development

to the natures of animals and things. Able to give their full development to

the natures of creatures and things, he can assist the transforming and

nourishing powers of Heaven and Earth. Able to assist the transforming and nourishing powers of Heaven and

Earth, he may with Heaven and Earth form a ternion.

·

Sincerity becomes apparent. From being apparent, it becomes manifest.

From being manifest, it becomes brilliant. Brilliant, it affects others.

Affecting others, they are changed by it. Changed by it, they are transformed.

It is only he who is possessed of the most complete sincerity that can exist

under heaven, who can transform.

·

It is characteristic of the most entire sincerity to be able to foreknow.

When a nation or family is about to flourish, there are sure to be happy omens;

and when it is about to perish, there are sure to be unlucky omens.

·

Sincerity is that whereby self-completion is effected, and its way is

that by which man must direct himself.

·

Sincerity is the end and beginning of things; without sincerity there

would be nothing. On this

account, the superior man regards the attainment of sincerity as the most

excellent thing.

·

To entire sincerity there belongs ceaselessness. Not ceasing, it continues long. Continuing

long, it evidences itself. Evidencing itself, it reaches far. Reaching far, it

becomes large and substantial. Large and substantial, it becomes high and

brilliant. Large and substantial; this is how it contains all things. High and

brilliant; this is how it overspreads all things. Reaching far and continuing

long; this is how it perfects all things. So large and substantial, the

individual possessing it is the co-equal of Earth. So high and brilliant, it

makes him the co-equal of Heaven. So far-reaching and long-continuing, it makes

him infinite. Such being its nature,

without any display, it becomes manifested; without any movement, it produces

changes; and without any effort, it accomplishes its ends.

·

The way of Heaven and Earth may be completely declared in one sentence:

They are without any doubleness, and so they produce things in a manner that is

unfathomable.

·

How great is

the path proper to the Sage! Like overflowing water, it sends forth and

nourishes all things, and rises up to the height of heaven. All-complete is its

greatness! It embraces the three hundred rules of ceremony, and the three

thousand rules of demeanor. It waits for the proper man, and then it is

trodden. Hence it is said, "Only

by perfect virtue can the perfect path, in all its courses, be made a

fact."

·

The superior

man honors his virtuous nature, and maintains constant inquiry and study, seeking

to carry it out to its breadth and greatness, so as to omit none of the more

exquisite and minute points which it embraces, and to raise it to its greatest

height and brilliancy, so as to pursue the course of the Mean. He cherishes his

old knowledge, and is continually acquiring new. He exerts an honest, generous

earnestness, in the esteem and practice of all propriety. Thus, when occupying

a high situation he is not proud, and in a low situation he is not

insubordinate. When the kingdom is well governed, he is sure by his words to

rise; and when it is ill governed, he is sure by his silence to command

forbearance to himself.

·

To no one but

the Son of Heaven does it belong to order ceremonies, to fix the measures, and

to determine the written characters.

·

The

institutions of the Ruler are rooted in his own character and conduct, and

sufficient attestation of them is given by the masses of the people. He

examines them by comparison with those of the three kings, and finds them

without mistake. He sets them up before Heaven and Earth, and finds nothing in

them contrary to their mode of operation. He presents himself with them before

spiritual beings, and no doubts about them arise. He is prepared to wait for

the rise of a sage a hundred ages after, and has no misgivings. His presenting himself with his institutions

before spiritual beings, without any doubts arising about them, shows that he

knows Heaven. His being prepared, without any misgivings, to wait for the rise

of a sage a hundred ages after, shows that he knows men.

·

All things are nourished together without their injuring one another. The

courses of the seasons, and of the sun and moon, are pursued without any

collision among them. The smaller energies are like river currents; the greater

energies are seen in mighty transformations. It is this which makes heaven and earth so great.

·

It is only

he, possessed of all sagely qualities that can exist under heaven, who shows

himself quick in apprehension, clear in discernment, of far-reaching

intelligence, and all-embracing knowledge, fitted to exercise rule;

magnanimous, generous, benign, and mild, fitted to exercise forbearance;

impulsive, energetic, firm, and enduring, fitted to maintain a firm hold;

self-adjusted, grave, never swerving from the Mean, and correct, fitted to

command reverence; accomplished, distinctive, concentrative, and searching,

fitted to exercise discrimination. All-embracing is he and vast, deep and

active as a fountain, sending forth in their due season his virtues.

All-embracing and vast, he is like Heaven. Deep and active as a fountain, he is

like the abyss. He is seen, and the people all reverence him; he speaks, and

the people all believe him; he acts, and the people all are pleased with him.

·

It is only the individual possessed of the most entire sincerity that can

exist under Heaven, who can adjust the great invariable relations of mankind,

establish the great fundamental virtues of humanity, and know the transforming

and nurturing operations of Heaven and Earth; — shall this individual have any being or anything beyond himself on

which he depends? Call him man in his ideal, how earnest is he! Call him an

abyss, how deep is he! Call him Heaven, how vast is he! Who can know him, but

he who is indeed quick in apprehension, clear in discernment, of far-reaching

intelligence, and all-embracing knowledge, possessing all Heavenly virtue?

·

It is the way of the superior man to prefer the concealment of his

virtue, while it daily becomes more illustrious, and it is the way of the mean

man to seek notoriety, while he daily goes more and more to ruin. It is characteristic of the superior man,

appearing insipid, yet never to produce satiety; while showing a simple

negligence, yet to have his accomplishments recognized; while seemingly plain,

yet to be discriminating. He knows how

what are distant lies in what is near. He knows where the wind proceeds from.

He knows how what is minute becomes manifested. Such a one, we may be sure,

will enter into virtue.

·

The superior man examines his heart, that there may be nothing wrong

there, and that he may have no cause for dissatisfaction with himself. That wherein the superior man cannot be

equaled is simply this — his work which other men cannot see.

·

The superior

man, even when he is not moving, has a feeling of reverence, and while he

speaks not, he has the feeling of truthfulness.

·

It is said in the Book of

Poetry, "In silence is the offering presented, and the spirit approached

to; there is not the slightest contention." Therefore the superior man

does not use rewards, and the people are stimulated to virtue. He does not show

anger, and the people are awed more than by hatchets and battle-axes.

·

Among the

appliances to transform the people, sound and appearances are but trivial

influences.

·

The Great Learning

Things have their root and their branches.

Affairs have their end and their beginning. To know what is first and what is last will lead near to what is taught in the

Great Learning.

·

What the great learning teaches is to illustrate

illustrious virtue; to renovate the people; and to rest in the highest

excellence.

The point where to rest being known, the object of pursuit is then determined; and, that being determined, a calm unperturbedness may be attained to. To that calmness there will succeed a tranquil repose. In that repose there may be careful deliberation, and that deliberation will be followed by the attainment of the desired end.

The point where to rest being known, the object of pursuit is then determined; and, that being determined, a calm unperturbedness may be attained to. To that calmness there will succeed a tranquil repose. In that repose there may be careful deliberation, and that deliberation will be followed by the attainment of the desired end.

·

Things have their root and their branches. Affairs

have their end and their beginning. To know what is first and what is last will

lead near to what is taught in the Great Learning.

·

The ancients, who wished to illustrate illustrious

virtue throughout the Kingdom, first ordered well their own states. Wishing to

order well their states, they first regulated their families. Wishing to

regulate their families, they first cultivated their persons. Wishing to

cultivate their persons, they first rectified their hearts. Wishing to rectify

their hearts, they first sought to be sincere in their thoughts. Wishing to be

sincere in their thoughts, they first extended to the utmost their knowledge.

Such extension of knowledge lay in the investigation of things.

Things being investigated, knowledge became complete. Their knowledge being complete, their thoughts were sincere. Their thoughts being sincere, their hearts were then rectified. Their hearts being rectified, their persons were cultivated. Their persons being cultivated, their families were regulated. Their families being regulated, their states were rightly governed. Their states being rightly governed, the whole kingdom was made tranquil and happy.

From the Son of Heaven down to the mass of the people, all must consider the cultivation of the person the root of everything besides.

Things being investigated, knowledge became complete. Their knowledge being complete, their thoughts were sincere. Their thoughts being sincere, their hearts were then rectified. Their hearts being rectified, their persons were cultivated. Their persons being cultivated, their families were regulated. Their families being regulated, their states were rightly governed. Their states being rightly governed, the whole kingdom was made tranquil and happy.

From the Son of Heaven down to the mass of the people, all must consider the cultivation of the person the root of everything besides.

·

·

What you do not want done to yourself, do not do to

others.

·

·

·

Recompense

hatred with justice, and recompense kindness with kindness

·

Chapter

XIV:36

·

Learning

without thought is labor lost; thought without learning is perilous.

·

Book

II, Chapter XV.

·

There

is the love of knowing without the love of learning; the beclouding here leads

to dissipation of mind.

·

Book

XVII, Chapter VIII.

·

Of

all people, girls and servants are the most difficult to behave to. If you are

familiar with them, they lose their humility. If you maintain a reserve towards

them, they are discontented.

·

A

man living without conflicts, as if he never lives at all.

·

A

scholar who loves comfort is not worthy of the name.

·

The

man of virtue makes the difficulty to be overcome his first business, and

success only a subsequent consideration.

·

When

you have faults, do not fear to abandon them.

·

The

superior man understands what is right; the inferior man understands what will

sell.

·

Guide

the people by law, subdue them by punishment; they may shun crime, but will be

void of shame. Guide them by example, subdue them by courtesy; they will learn

shame, and come to be good.

Ethics

One of the deepest

teachings of Confucius may have been the superiority of personal

exemplification over explicit rules of behavior. His moral teachings emphasized

self-cultivation, emulation of moral exemplars, and the attainment of skilled

judgment rather than knowledge of rules. Confucian ethics may, therefore, be

considered a type of virtue ethics. His teachings rarely rely on reasoned

argument, and ethical ideals and methods are conveyed indirectly, through allusion, innuendo, and even tautology. His teachings require examination and context to be understood. A

good example is found in this famous anecdote:

When the stables

were burnt down, on returning from court Confucius said, "Was anyone

hurt?" He did not ask about the horses. Analects X.11

By not asking

about the horses, Confucius demonstrates that the sage values human beings over

property; readers are led to reflect on whether their response would follow

Confucius's and to pursue self-improvement if it would not have. Confucius

serves not as an all-powerful deity or a universally true set of abstract

principles, but rather the ultimate model for others. For these reasons,

according to many commentators, Confucius's teachings may be considered a Chinese

example of humanism.

One of his

teachings was a variant of the Golden Rule, sometimes called the "Silver Rule" owing to its negative form:

"What you do

not wish for yourself, do not do to others." ”

Zi Gong [a

disciple] asked: "Is there any one word that could guide a person

throughout life?"

The Master replied: "How about 'reciprocity'! Never impose on others what you would not choose for yourself." Analects XV.24

The Master replied: "How about 'reciprocity'! Never impose on others what you would not choose for yourself." Analects XV.24

Often overlooked

in Confucian ethics are the virtues to the self: sincerity and the cultivation

of knowledge. Virtuous action towards others begins with virtuous and sincere

thought, which begins with knowledge. A virtuous disposition without knowledge

is susceptible to corruption, and virtuous action without sincerity is not true

righteousness. Cultivating knowledge and sincerity is also important for one's

own sake; the superior person loves learning for the sake of learning and

righteousness for the sake of righteousness.

Legacy

Confucius's teachings were later turned into an

elaborate set of rules and practices by his numerous disciples and followers,

who organized his teachings into the Analects. Confucius's disciples and his

only grandson, Zisi,

continued his philosophical school after his death. These efforts spread

Confucian ideals to students who then became officials in many of the royal

courts in China, thereby giving Confucianism the first wide-scale test of its dogma.

Two of Confucius's most famous later followers

emphasized radically different aspects of his teachings. In the centuries after

his death, Mencius and Xun Zi both composed important teachings elaborating

in different ways on the fundamental ideas associated with Confucius. Mencius (4th

century BC) articulated the innate goodness in human beings as a source of the

ethical intuitions that guide people towards rén, yì, and lǐ,

while Xun Zi (3rd

century BC) underscored the realistic and materialistic aspects of Confucian

thought, stressing that morality was inculcated in society through tradition

and in individuals through training. In time, their writings, together with the

Analects and other core texts came to constitute the philosophical

corpus of Confucianism.

Under the succeeding Han and Tang

dynasties, Confucian ideas gained even more widespread prominence. Under Wudi, the

works of Confucius were made the official imperial philosophy and required

reading for civil service examinations in 140 BC which was continued nearly

unbroken until the end of the 19th century. As Mohism lost

support by the time of the Han, the main philosophical contenders were

Legalism, which Confucian thought somewhat absorbed, the teachings of Laozi, whose

focus on more spiritual ideas kept it from direct conflict with Confucianism,

and the new Buddhist religion, which gained acceptance during the Southern and Northern Dynasties era.

Both Confucian ideas and Confucian-trained officials were relied upon in the Ming

Dynasty and even the Yuan Dynasty, although Kublai Khan

distrusted handing over provincial control to them.

During the Song

dynasty, the scholar Zhu Xi (AD 1130–1200) added ideas from Daoism and Buddhism into

Confucianism. In his life, Zhu Xi was largely ignored, but not long after his

death, his ideas became the new orthodox view of what Confucian texts actually

meant. Modern historians view Zhu Xi as having created something rather

different and call his way of thinking Neo-Confucianism.

Neo-Confucianism held sway in China, Japan, Korea, and Vietnam until the 19th

century.

The works of Confucius were first translated into

European languages by Jesuit missionaries in

the 16th century during the late Ming

dynasty. The first known effort was by Michele

Ruggieri, who returned to Italy in 1588 and carried on his translations while

residing in Salerno. Matteo

Ricci started to report on the thoughts of Confucius, and a team of Jesuits—Prospero Intorcetta, Philippe

Couplet, and two others—published a translation of several Confucian

works and an overview of Chinese

history in Paris in 1687.François Noël, after failing to persuade Clement XI that Chinese veneration of ancestors and Confucius did not constitute idolatry,

completed the Confucian canon at Prague in 1711,

with more scholarly treatments of the other works and the first translation of

the collected works of Mencius. It

is thought that such works had considerable importance on European thinkers of

the period, particularly among the Deists and

other philosophical groups of the Enlightenment who were interested by the

integration of the system of morality of Confucius into Western

civilization.

In the modern era Confucian movements, such as New

Confucianism, still exist, but during the Cultural Revolution,

Confucianism was frequently attacked by leading figures in the Communist Party of China. This

was partially a continuation of the condemnations of Confucianism by

intellectuals and activists in the early 20th century as a cause of the

ethnocentric close-mindedness and refusal of the Qing

Dynasty to modernize that led to the tragedies that befell China in the 19th

century.

Confucius's works are studied by scholars in many

other Asian countries, particularly those in the Chinese cultural sphere, such as

Korea, Japan, and Vietnam. Many of those countries still hold the traditional

memorial ceremony every year.

After travelling for many

years, Confucius returned to his homeland at the age of 68 and devoted himself

to teaching. He is said to have died in 479 B.C. at the age of 72–an auspicious

and magical number. He died without reforming the duke and his officials. But

after his death, his followers created schools and temples in his honour across

East Asia, passing his teachings along for over 2,000 years. (They also kept

his genealogy, and more than two million people alive today claim to be his

direct descendants!) At first, Confucian scholars were persecuted in some areas

during the Qin dynasty (3rd century B.C). But in the later Han dynasty (3rd

century B.C. to 3rd century A.D.), Confucianism was made the official

philosophy of the Chinese government and remained central to its bureaucracy

for nearly two thousand years. For a time, his teachings were followed in

conjunction with those of Lao Tzu and the Buddha, so that Daoism, Confucianism,

and Buddhism were held as fully compatible spiritual practices. Perhaps most

importantly, Confucius’s thought has been a huge influence on eastern political

ideas about morality, obedience, and good leadership.

Today millions of people still

follow Confucius’s teachings as a spiritual or religious discipline, and even

observe Confucian rituals in temples and at home. He is called by many

superlatives, including ‘Laudably Declarable Lord Ni’, ‘Extremely Sage Departed

Teacher’, and ‘Model Teacher for Ten Thousand Ages’. He is still a steadfast

spiritual guide.

Conclusion

We might find Confucian virtues a bit strange or

old-fashioned, but this is what ultimately makes them all the more important

and compelling. We need them as a corrective to our own excesses. The modern

world is almost surprisingly un-Confucian – informal, egalitarian, and full of

innovation. So we are conversely at risk of becoming impulsive, irreverent, and

thoughtless without a little advice from Confucius about good behavior and

sheep.

No comments:

Post a Comment