Under

development in Rural Sindh

Introduction

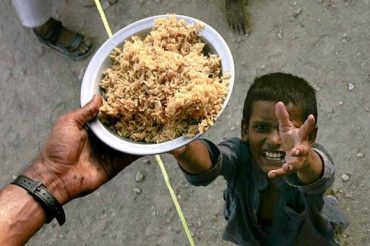

Poverty is a global affliction

affecting numerous countries in the developing world. Pakistan is home to

millions of people who live in extreme poverty. Poverty in Pakistan is on track

to decrease, but there is still work to be done. Although the latest economic

news is not good and one factor that mitigates poverty incidence is a strong

GDP growth .

With

approximately 200 million citizens, Pakistan ranks 147th out of 188 countries

in the Human Development Index (HDI). Reports on poverty in

Pakistan show that as much as 40 percent of the population–roughly the size of

the population of Florida, California and New York combined–live beneath the

poverty line.

The Multidimensional Poverty Index (MPI) report by the Pakistan

Ministry of Planning, Development and Reform in June 2016 shows that 39 percent

of Pakistanis live in multidimensional poverty. The MPI methodology, developed

by UNDP and the Oxford Poverty and Human Development Initiative in 2010, uses a

broader concept of poverty by reflecting people’s deprivations related to

health, education and standard of living in addition to income and wealth.

The good news is that

poverty in Pakistan decreased by 15 percent in the past decade, but, given the

grim lows overall, this figure is less than encouraging. In order to alleviate

poverty, policymakers need to focus on achieving the U.N. Sustainable

Development Goals (SDGs) by 2030. Although it is a big challenge for an

underdeveloped country like

Pakistan, meeting the SDGs is important since they provide the best

possible integrated way for inclusive growth, peace and development.

Poverty

levels in Sindh

Poverty

in Sindh’s capital stood at 4.5% in 2014-15, decreasing the poverty ratio for

the province as a whole. 2015 floods,

coupled with egregious governance, have worsened living standards in Sindh

where 75% of the population in rural areas is now living in abject poverty. The

overall poverty ratio of 43.1%, compiled by aggregating figures from urban and

rural areas, does not actually convey the real picture of Sindh most of which

is rural.

The

province has been categorized second poorest after Baluchistan among all the provinces

and regions of Pakistan, excluding the militancy-hit Federally Administered

Tribal Areas. Baluchistan’s 84.6% rural population lives below the poverty

line, according to a United Nations report.

The

statistics revealed in the recently released study on multidimensional poverty

in Pakistan were discussed at length at a seminar organized by the UN’s Food

and Agriculture Organization (FAO) and International Labour Organization. The

UN report for 2014-15 titled “Multidimensional Poverty in Pakistan” shows

poverty in urban areas of Sindh at 10.6% but an alarming 75.5% in rural areas,

which constitute a major chunk of the province.

In

Sindh’s Umarkot district, where half of

the population is Hindu, 84.7% people lived under the poverty line. In 2012-13,

the figure stood at 80.7% and in 2010-11 75.9%. In Thatta, 78.5% people live in

poverty while the rate was 76.5% in 2012-13. Few districts in Sindh have seen

progress in alleviating miseries of people. Some showed a slight improvement

one year but the situation deteriorated the next year. A slight change in

weather or an untoward incident pushes the people back to extreme poverty.

In

Tharparkar, some progress was achieved over the years but the district slipped

back into the negative trend. In 2008-9, 92.1% lived in poverty, 91.6% in

2010-11 and 84.6% in 2012-13. But in 2014-15, the figure increased to 87%. Statistics

for Nawabshah, Naushero Feroz and Mirpurkhas also show similar trends. However

Jamshoro is among a few districts witnessing a steady improvement over the

years.

In

2008-09, 72.4% population of the district was living below the poverty line but

it reduced to 70.7% in 2010-11 and 67% in 2012-13. In 2014-15, the district

registered a poverty rate of 55.6% – faring better than the provincial average.

With

better job and business opportunities, Karachi maintained its reputation as the

‘mother of the poor’. Poverty in Sindh’s capital stood at 4.5% in 2014-15,

decreasing the poverty ratio for the province as a whole. In, 2010.5% of

Karachi’s population lived below the poverty line.

Poverty Assessment

The poverty head count ratio in the countryside is almost double

that of urban areas. Rural Sindh has around 50 per cent of the population, and

shares about 30 per cent of the province’s GDP.

The state of affairs is attributed to slow growth in the

province’s hinterlands, which has led to widespread rural poverty. This is a

serious concern not only for the welfare of the dwellers of the countryside,

but also for the economic and social stability of the province.

The World Bank has observed a 0.5 per cent decline on average in

per capita income in rural Sindh every year since 1999. The report also says

that 50 per cent of the population of rural areas lives below the poverty line,

and suffers from low per capita incomes and calorie intake, as well as

unemployment and inadequate access to education, sanitation and health

facilities, an unhygienic environment, and insecure access to natural

resources.

The concentration of the poor is highest among households that

have at their head an unpaid worker, share-cropper, or owner/cultivator with

less than two hectares of land. A major study recently conducted found that

36.3 per cent of the respondents in rural Sindh consumed less than 1,700

calories a day, while another 25 per cent consumed between 1,700 to 2,100

calories a day.

Water and Agriculture

Since

the economy of Sindh is largely agrarian the economic development of the

province depends largely on the development of its agriculture sector. Rural

Sindh has been hit hard by disasters including droughts and floods and the

majority of rural population has been pushed below the poverty level.

The

irony is that both sources of livelihood and employment opportunities for rural

inhabitants in Sindh are shrinking. As a result, the unemployed youth move to

cities for jobs but the urban employment market is already oversaturated.

Sindh

has fertile soil and is rich in fuel and mineral deposits but has a rural

poverty graph that continues to rise. In the absence of proper land-use

regulation, unscrupulous land developers have been allowed to convert

agricultural land near urban centers into housing schemes. These agricultural

lands were traditionally used for growing vegetables and other cash crops.

Urban

Sindh, which consists mainly of Karachi, Hyderabad, Sukkur, Nawabshah,

Shikarpur and Larkana, comprises 48 per cent of the provincial population. It

is also showing a decline in economic growth. In addition, the urban areas of

Sindh continue to receive an influx of population leading to stress in the

infrastructure and a further increase in the level of unemployment.

Rural inhabitants are mainly dependent on agriculture, with those

in arid zones on animal rearing, and those along the coastal belt on fishing.

But the constant shortage of water in Thatta, Badin, Umerkot, and parts of

Sanghar, Mirpurkhas, Dadu districts, and surprisingly even in some pockets of

the Rohri canal system in Khairpur district, is the main factor behind

increased poverty.

This is due to the mismanagement of water. Independent economists

and the World Bank have held both the draught and the policymakers responsible

for low agricultural production. Devastating rains a few years ago and flood

damages, which damaged crops in some areas, (exposed lack of drainage

facilities) have increased poverty

levels in some areas.

Official figures suggest that poverty is on the rise in Badin and

Thatta districts due to sea intrusion, which is causing a permanent or seasonal

submerging of irrigated cultivable lands. Lands that are not under direct

threat of sea intrusion, but where there is a constant shortage of irrigation

water, or an irregular supply of it since the last 10 years, have virtually

ruined the agriculture.

Ground realities suggest that water shortage in Badin and Thatta

districts, as well as in Umerkot and a major portion of the command area of

Taluka Johi and Khairpur Nathanshah in Dadu district, will not improve, and actually

further deteriorate.

While the availability of water in other parts of Sindh may be

comparatively better, the crop yield is still low, mainly because of soil

erosion and over-irrigation. Besides this, farm inputs are costly, quality

seeds are not available, fertilizers are adulterated and pesticides spurious.

Urban employment

Employment opportunities

in Karachi, Hyderabad, Sukkur and other urban areas of Sindh started declining

in the 1990s as a result of a flight of capital and industry from the urban

areas due to a serious law and order situation. Some rural industry like cotton

ginning also shifted from Sindh to South Punjab

Feudal structure and land ownership

A World Bank report titled, Securing Sindh’s future prospects and

challenges, noted that, “given its feudal traditions, progressive ideas and

reforms have always taken more time to take roots in the interior of Sindh than

in most other areas of Pakistan. Sindh has the highest incidence of absolute

landlessness, highest share of tenancy and lowest share of land ownership in

the country.

“Wealthy landlords with holdings in excess of 100 acres form less

than one per cent of all farmers in province, and own 150 per cent more land

than combined holdings of 62 per cent of small farmers with holdings less than

five acres.”

The

rural parts of Sindh are in a state of abject poverty. One of the major reasons

is that most of the population there does not own or control assets like good

quality land — the prime asset in rural settings. There is a highly uneven

distribution of land ownership in Sindh. Land reforms have never been on the

agenda of any government.

Access

to land, which is the basic factor of production, is crucial to reduce poverty

in rural areas. According to the Agricultural Census of Pakistan, cultivated

land is unequally distributed in Pakistan. About 47 per cent of the farms are

smaller than two hectares, accounting for only 12 per cent of the total

cultivated area. In Sindh, where the rural society is dominated by a feudal

elite, the proportion of small farms is just above a third. In fact, the

landholdings of the feudal families in Sindh have multiplied instead of having

decreased. Although economic vulnerability has not been comprehensively

measured for Sindh, there are indications that vulnerability differs

significantly across agro-climatic zones and over two-thirds of the households

in rural Sindh may be classified as economically vulnerable. Poverty has become

a major issue in rural Sindh, where 50 per cent of the population lives below

the poverty line and suffer from low calorie intake, low per capita income,

unemployment, inadequate access to education, sanitation, health facilities and

an unhygienic environment. More importantly, these people are the most

vulnerable to shocks.

Public services

The poor also suffer from low quality public services. They have

relatively lower access to safe drinking water and sanitation facilities. For

example, while 31 per cent of the rural population of the country is connected

to the drainage system, the same is true for only 14 per cent of Sindh’s rural

populace. Only 10 per cent of them have access to proper sanitation facilities.

In villages, excreta accumulations can be found outside homes, and

this becomes a major source for spread of infectious and waterborne diseases.

Women, children, the elderly, and those who are already suffering from

diseases, are largely affected.

Education

Pakistan belongs

to those nations who have the world's worst literacy rate, which is the main

reason for its slow agricultural growth and sluggish economy The literacy rate for Pakistan in a 2012 consensus was 56%,

which includes both males and females from both rural and urban areas. A 56%

literacy rate is very low; this means that almost half of the country is

illiterate and can contribute very little to economic development because the

major contribution in that area is made through education

According to the United Nations Educational, Scientific

and Cultural Organization (UNESCO), Pakistan at 55% has one of the lowest

literacy rates in the world, and stands 160th among world nations. Many schools

and colleges are entering the teaching profession, particularly in major

cities, but those living in rural areas record a greater loss.

Sindh is

Pakistan's most populated province, with a population of over 25 million

people. Its literacy rate is below 50% in rural areas. In 1972 and 1998, it was

30.20% and 45.30%. Similarly, in 2010, 2013 and 2014, it was 69%, 60% and 56%.

Overall, many children are deprived of education, as evidenced by the greater

percentage of child labor. .Adult literacy rates for Pakistan are presented as

follows :

Adult Literacy Rate in Rural Areas [2010-11] [15 plus age Cohort]

Overall

|

Male

|

Female

|

|

Pakistan

|

44.9

|

60.0

|

29.9

|

Punjab

|

48.7

|

60.9

|

36.7

|

Sindh

|

38.6

|

48.0

|

17.2

|

Khyber Pakhtunkhwa

|

42.5

|

62.4

|

23.8

|

Baluchistan

|

30.2

|

49.2

|

9.0

|

Source: SPDC

estimates based on household level data

of PSLM 2010-11

|

|||

Health

According to UN estimates, poor sanitation costs the country $4.2

billion, or 6.3 per cent of its GDP. According to estimates from the United

States Agency for International Development, around 250,000 children die each

year in Pakistan due to waterborne diseases. About 40 per cent of hospital beds

in Sindh are occupied by patients suffering from water and sanitation diseases

like typhoid, cholera, dysentery and hepatitis, which are responsible for

one-third of total deaths as well.

rural areas in terms of health outcome indicators such as malnutrition, infant mortality, maternal mortality and immunisation.

Geographic coverage and accessibility of public health services in rural

areas is also very poor which has serious implications for people’s health. Federal and provincial governments have made attempts to introduce

alternate models of service delivery in the form of public-private

partnerships that have achieved some success. Moreover, vertical

programmes of the federal government have also played an important role in supplementing the efforts of the provincial

governments. However,

the dismal situation of health indicators demands that a more concerted effort needs be made, possibly in every domain of the health sector

Meanwhile, more than 55 per cent of public elementary schools do

not have water connections or toilet facilities. Given that rural poverty in

Sindh is higher than the country average, the rural poor suffer from an

especially severe lack of critical facilities, which is likely to have a strong

impact on their health. Therefore, sanitation and hygiene are fundamental to

broader rural development.

Haris Gazdar, Pakistan’s lead researcher for

Leveraging Agriculture for Nutrition in South Asia (LANSA) and director of

CSSR, reported findings from the Women’s Work in Agriculture and Nutrition

(WWN) Survey 2015-16. The survey found that 46 per cent of children between 0-3

months are stunted in rural Sindh.

Oil Companies

The

province is rich in natural resources, having huge reserves of oil, gas and

coal. It has two seaports one of which is in Karachi — the financial hub and

business nerve centre of Pakistan. Some of its districts have industrial zones

but these have been hit by lawlessness.

Sindh

accounts for almost 72 per cent of the total oil and gas production of the

country, but its hinterland is still one of the backward regions with soaring

poverty, high rate of unemployment and widening inequalities between rural and

urban Sindh. When oil and gas was exploited, it was believed that poverty would

become history and Sindh would be affluent like the Gulf emirate of Dubai. But

this hope has remained a mere pipedream.

Oil companies are not fulfilling their corporate responsibility,

as they have to spend one per cent of their earnings on local development and

establish schools, hospitals and construct roads. Nothing meaningful is

happening. It is an irony that while Sindh produces almost 72 per cent of the

country’s total oil and gas, its hinterland is still one of the more backward

regions in the country, with soaring poverty, high unemployment, and widening

rural-urban inequality. For instance, look at the plight of Badin district,

which produces 60 per cent of the country’s oil, but ranks at 90 in the Human

Development Index of districts of Pakistan.

Social

Changes in rural Sindh

Arif Hasan states

“The change that I have observed and which has

been articulated by the groups I interacted with, is enormous and that too in

10 years. The most visible and important change is the presence of women in

development and political discourse. They are employed in NGO offices, they

manage development programs, they are social activists and the majority of them

are from the rural areas. In some of the remote villages I visited, there were

private schools and beauty parlors run by young village women. Blocking of

roads to protest against the “high handedness” of the local landlords,

bureaucratic inaction, and/or law and order situations, has become common. Women

participate in these demonstrations and in some cases these blockages have been

carried out exclusively by them.

Discussions

with groups on the issue of free-will marriages were also held. The vast

majority of individuals were in favour of such marriages even if they violated

caste divisions. However, they felt that it is the parents that have to change

so as to make such marriages conflict free. The non-availability of middle

schools for girls was also discussed. Surprisingly, the village communities had

no problem with the girls studying with the boys in the male middle schools. In

addition, discussions with the Sindh Rural Support Organisation’s (SRSO) women

groups, which consist of the poorest women in a village, revealed that about 20

per cent of them had mobile phones and almost all of them watched television

although around 30 per cent households actually own a TV.

The

other major change that has taken place is in physical mobility. The number of

transport vehicles has visibly increased manifold. The desire to migrate to an

urban area is second only to the desire to get children educated. In all the

areas visited, many families had members working in Karachi. Previously, people

were scared to go to Karachi because of the violence in the city. But now they

have friends and relatives over there and protection as well. This partly

explains the rapidly increasing numbers of Sindhi speakers in the city. In

addition, it was constantly stated that those haris who had relatives in

urban centers and received remittances were better off and were able to send

their children to the cities for better education and hence a better future.

Many

of the above changes are related to the changed landlord-hari

relationship. Unlike before, the haris spoke openly against the local

landlord. In most cases, they also stated that they did not want to remain haris

but to get regular jobs, operate rickshaws and do small businesses. Their

perception of the landlord has also undergone a change. He no longer comes

regularly to the area. He has a city wife and his children have little or no

link with the land. Given his changed nature, he can no longer effectively

settle “disputes”. His absence and changed nature has provided the hari

families with opportunities for physical and social mobility. Dr Sono

Khangharani of the SRSO also made an important observation by pointing out that

an increasing number of “low caste” young men and women were studying with the

children of powerful rural families in the elite universities of Pakistan.

The

changes described above are the natural outcome of new technologies, expanding

trade and commerce and the media revolution. But more so, they are the result

of the Government of Pakistan’s education system, in spite of its bad quality.

Young men and women have returned from universities and colleges in the larger

cities armed with new experiences and knowledge and a vision of a new world.

Peasant women have gone to the village school and learnt to read and write. It

must also be noted that in many cases, the village elders and a new breed of

politicians are also responding to this change. Recently, an elder from a very

small and conservative village visited me with CVs of three village girls who

had done their BA with the request that I should get them jobs with some NGO or

government program.

However,

according to the people we met, the system is fighting back. They are of the

view that the tribal conflicts that are taking place are being created to break

the unity of the people; that problems are also created so that the chiefs and

their representatives can assert their power in the process of solving them;

that the law and order situation in the rural areas is created to drive away

‘genuine’ activists; and that much of the migration to the urban areas is the

result of such violence. Land is also being acquired by the powerful at all

costs so as to consolidate their power further. It is felt that they are

sending their children and relatives into the bureaucracy and the police so as

to both acquire and control this land. The mullahs meanwhile, preach against

minority Muslim sects, women’s studying and working and against the “fahashi”

of free-will marriages. And, everyone from the wadera to the hari is

armed. It is obvious that the old order cannot come back for the change is too

big to be contained.”

Causes of Poverty

The rural parts of Sindh are in a state of abject poverty.

One of the major reasons is that most of the population there does not own or

control assets like good quality land — the prime asset in rural settings.

There is a highly uneven distribution of land ownership in Sindh. Land reforms

have never been on the agenda of any government

Poor governance is the key underlying cause of poverty

in Pakistan. Poor governance has not only enhanced vulnerability, but is the prime cause of low business confidence, which in turn translates into lower investment

levels and growth.

Governance problems have also resulted

in inefficiency in provision of social services, which has had serious

implications for human development in the country. The lack of public

confidence in state institutions, including the police and judiciary, have eroded their legitimacy and directly contributed to worsening conditions of public security

and law and order during the

1990s.

With regard

to economic factors,

decline in the Gross Domestic

Product (GDP) growth

rate is the immediate cause

of the increase in poverty

over the last decade. The causes of the slowdown

in growth may be divided

into two categories, i.e.

Structural

and others.

With the former being more long-term

pervasive issues, which have persisted because of deteriorating governance. Among the structural

causes, the burgeoning debt burden and declining

competitiveness of the Pakistan economy

in the increasingly skill-based global

economy are the most important. While the former occurred due to economic

mismanagement, the latter was because of Pakistan's low level of human development.

The existence

of pervasive poverty,

wherein a significant proportion of the population remains

poor over an extended period of time is strongly

linked with the structure of society. Cultivated land is highly unequally distributed in Pakistan. About 47 percent

of the farms are smaller than 2 hectares, accounting

for only 12 percent of the total cultivated area. Access

to land, which is the basic factor

of production, is crucial to reduce poverty

in rural areas. Pervasive inequality

in land ownership intensifies the degree of vulnerability of the poorest

sections of rural society, because

the effects of an unequal land distribution are not limited

to control over assets.

The structure of rural society,

in areas where land ownership

is highly unequal,

tends to be strongly hierarchical, with large landowners

or tribal chiefs exercising considerable control over the decisions, personal

and otherwise, of people living in the area under

their influence, as well as over their access to social infrastructure facilities.

Recommendations

Sindh needs rapid development in agriculture coupled with

genuine land reforms, agro-based industries, small and medium industries and

the development of the information technology sector at the provincial and

district levels. There is strong potential to create jobs and self-employment

at both the provincial and district levels. This potential to create jobs and

self-employment needs to be explored further. Growth must be accompanied by

measures that ensure social development, which takes into account economic,

political and social dimensions. The rural population must be provided the

opportunity to fully harness and participate in the growth process and develop

their capacity to take benefits from it while giving special attention to rural

Sindh and bringing it into the mainstream.

Water availability also needs to be improved, so to must be

the sharing of water on a canal where the down stream users are usually

deprived of much water.

Labor policies and laws needed to apply to female agricultural

workers (who perform the bulk of the work).

The need for forming women cooperatives at the state level for greater

financial inclusion and political representation of women is crucial. The need

for strong policy instruments and political will to ensure landownership and

land titles for women. Actions needed to be

taken to ensure that women could access and use credit, especially

microfinance. Actions needed to be taken to ensure that women could access and

use credit, especially microfinance.

Strategic

opportunities are recommended which include political championing at the

highest level to leverage nutrition into development priorities across party

lines; technical support to cohesively define nutrition priorities across

sectors and across urban and rural Sindh; strengthen governance; integration of

nutrition within the operational budgets of key sectors to have a better chance

of maintaining continuity; improve effectiveness of central convening

structures; strengthen vertical accountability within sectors; address

inequities in food insecurity and long-term disaster mitigation and recovery.

Oil companies are not

fulfilling their corporate responsibility, as they have to spend one per cent

of their earnings on local development and establish schools, hospitals and

construct roads. This should be ensured.

WB Project: Apr., 13, 2019: The

World Bank has downgraded its rating of a $433 million project – launched

nearly two years ago to reduce stunting in Sindh – to “moderately

unsatisfactory” amid the provincial government claiming better performance in

its statistics. The Bank has lowered the ratings of the progress of achieving

the project’s objectives as well as the pace of its implementation, according

to documents released by the bank on Thursday. The rating of the achievement of

objectives has been reduced to “moderately satisfactory” and the implementation

progress to “moderately unsatisfactory”. Of the total cost of $433 million, the

World Bank had approved a $61.62 million loan in May 2017 but linked the

disbursements to achieving the agreed targets. Because of the provincial

government’s poor performance, the bank has disbursed only $5 million so far. The

project was launched to reduce the stunting rate among children below five

years of age and focused on the most affected districts in Sindh. However, the

report shows that the provincial government tried to exaggerate its performance

in some indicators There was no progress

in the reduction of the stunting rate among children under five in the affected

districts. The bank stated in its report that 48% of children under five were

still suffering from stunted growth until the end of January 2019. The target

is to bring it down to 43% by December 2021. There was also no progress towards

the goal of increasing the percentage of children aged between six and 23

months who received appropriate liquids and solid, semi-solid or soft food for

the targeted minimum number of times. In 2014, only 8.9% of children in this

age bracket received a minimum acceptable diet — a ratio that remains unchanged

even after five year, according to the report. Under the bank’s financing

component, there is also a plan to distribute 2.7 million micro-nutrient

sachets for children up to two years of age till December 2021. Only 682,000

sachets have been distributed till January this year. To increase protein

intake and nutrition among children, the bank had also prepared a plan to help

setting up of small poultry farm units and community fish ponds. Against the

target of 26,000 households establishing backyard poultry farms and raising

goats, so far only 822 households have managed to do this. A target was set to

help establish 2,600 community fish ponds by December 2021 but so far only 40

have been set up. Around 3.5 million children between the ages of three and

five years were required to attend early childhood education. There has been no

progress towards this goal.

Education Sector:

Apr., 23, 2019:

The Sindh government

budget for the fiscal year 2018-19 witnessed an increase in spending

on education, with the Rs208.23 billion allocated for the education sector

showing an increase in spending of 14.67% from the outgoing fiscal year.

Since the incumbent ruling party in

Sindh took the reins of power years ago, budgetary allocations kept increasing every year compared to previous years, while

education standards remained stagnant, or rather, deteriorated. For instance,

an estimated 52%

of children in Sindh are still out of school. Despite billions of rupees being

‘spent’ every year on education by the Pakistan Peoples Party’s (PPP)

provincial government, in addition to money spent by international donors over

the last 11 years, the ground reality remains depressing and contrary to the

claims made by the Sindh government.

The ruling elites of

Sindh translate increased literacy to be a danger to their power structure,

which is essentially based on feudalism and dynastic politics. Increased

literacy will enlighten the citizenry with more tools for critical thinking and

informed decision-making skills, which is considered a threat to the very

dynastic political structure that is being maintained in Sindh. The PPP-led

government is afraid of such a social change, which may render it powerless.

To have a clear understanding of the

gravity of the problem, it is imperative to dissect the long 11 years of PPP in Sindh with regard only to the education

sector. It is very unfortunate that the Sindh government vociferously cries a

shortage of funds, which is what it blames for why it could not improve the

standards of education, including increasing the literacy rate, providing a

better quality of education, training teachers and so on. Above all, it has

completely failed to stop the deadly practice of unfair means or cheating in

exams, which is blatantly endangering the future of our younger generations.

However, the fact

remains that the Sindh government could not utilise the allocated budget for Special

Education, Sindh Technical Education and Vocational Training Authority

(STEVTA), Universities and Boards, and so on. During the last eight months of

the current fiscal year, utilisation of the allocated budget has been

negligible. Out of the Rs5 billion allocated for college education boards for

48 ongoing schemes with different interventions, unfortunately a meagre 16% of

the budget has been utilised over the past eight months.

The Chief Minister of Sindh allocated Rs9.598 billion for the Sindh Education Foundation

(SEF), with the intention to expand 2,400 schools and reach around 650,000

students. However, it has not moved past 550,000 students, as compared to

Punjab where three million students are enrolled under the foundation. This

year, the SEF received a large number of applications for the Adoption Program

but failed to execute it, because the Secretary School Education and Literacy

Department Qazi Shahid Pervaiz could not convene a board meeting over the last

five months.

Sindh has a total of 42,383 public schools, a number that has declined from 47,557

in 2011. Most schools, around 95%, only offer primary education. Given the

situation, dropping out after primary level becomes unavoidable. Meanwhile, the

Sindh government has completely failed to share a roadmap to overcome this gap.

The curriculum being followed is from

2007, while the last review was in 2012, for which the books have not yet been

printed. The Information and Communication Technologies (ICT) curriculum

belongs in the 19th century, and though the Early Childhood

Curriculum (ECE) was launched in a five-star hotel years ago . Still 10th grade

the medium of education is either Sindhi or Urdu, but higher secondary and college education in

Sindh is completely in English. This sudden change in the language of

instruction at higher grades creates trouble for the children

The Standardised

Assessment Test (SAT), which used to take place for students of class five and

eight, has also been suspended as most students who took the test failed.

Instead of improving the quality of teaching or re-examining the test itself,

the SAT process was suspended.

Meanwhile, there is

no accountability when it comes to the performance of teachers beyond

attendance, which is taken once a month, as this is part of the Reform Support

Unit (RSU) project in which someone visits and checks attendance through a

biometric device. This RSU project remains partly dysfunctional due to a lack

of funds, as foreign funding has been stopped.

Regarding the

management structure, there are currently two directorates that are

operational, while a third one is being planned to be setup for ECE. This means

each government school building and operations will be managed by three

different directorates. The consolidation policy of Sindh clearly remains a

failure. It is evident that the challenges are immense, though certain steps

are essential for improving Sindh’s educational system.

The SEF needs radical changes –

including budgetary – to increase enrolment, while the Education Department

needs to make existing public schools fully functional. The Private Schools Network (PSN) should be taken onboard (through

legislation) to run second shifts for secondary schools, and for this the

government should provide the PSN a subsidy per child. This is needed on a war

footing basis if we are to ensure Sindh’s children get a secondary education.

The process should be announced and published once a year to streamline the

academic year and ensure increased enrolment.

A curriculum board

should also be formed with an open and transparent process like that in Khyber

Pakhtunkhwa (K-P). When it comes to teachers, their performance – alongside the

principal’s – should be linked with the result of the school unit, while

their hiring should be carried out through independent bodies to ensure merit.

The college merger process should be carried out as per the judgement of the

High Court, while one school unit should obviously be managed by one head

instead of four different ones.

For examination

boards, the government should constitute a commission for managing, overseeing

and recommending measures related to examinations from primary to intermediate

levels. It will help improve education standards in the province and prohibit

cheating in exams.

Donor agencies such as the US Agency

for International Development (US AID), the EU, the United Nations Educational, Scientific and

Cultural Organisation (UNESCO) and the Gates Foundation should also be

convinced to work in liaison with the federal government for funded projects

instead of directly engaging at the provincial level, for I am a witness to how

foreign funding is being wasted here.

Sindh is lagging behind in achieving

the United Nations’ Sustainable Development goals and fulfilling the obligation

of free education under Article 25-A. At the pace with which the Sindh government is

working in the name of ‘reforms’, and with millions of children out of school,

we can only pray for a miracle to change the fate of the children of Sindh.

No comments:

Post a Comment